Japan is a country bursting with history, rich traditions, and a unique cultural identity. Among its most iconic symbols is sake. Delicate, aromatic, flavorful—sake is more than just a drink. It’s an experience brimming with depth, rituals, and history. It mirrors the meticulous nature of the Japanese people, their passion for refinement, and their profound connection to nature.

Take a sip. You’re stepping back in time. For over a thousand years, this cherished beverage has been woven into Japanese rituals, celebrations, and everyday life. Its beginnings are shrouded in ancient tales and traditional practices. Yet it has gracefully evolved, embracing modern methods while staying true to its roots. Just as cherry blossoms bloom in spring and red maples capture the essence of fall, sake embodies the rhythmic cycles of Japan’s landscape. It reflects the deep bond between people, culture, and the environment.

Sake’s Importance in Japanese Culture

From the meticulous selection of rice grains to the poetic nature of the brewing process, the production of sake is an art form. The precision required at every step is a testament to the dedication and reverence with which the Japanese approach their crafts. But beyond the production, lies an equally deep-seated culture of consumption. The act of drinking sake is not just about savoring its flavors but about immersing oneself in its history, traditions, and the shared collective experience of a nation.

The historical tapestry of sake is enriched with stories of emperors, samurais, and common folks, each weaving their own narrative into this ever-evolving culture. From its divine connection in Shinto rituals to its cherished place in village festivals and its prominent role in modern urban settings, sake stands as a beacon of Japan’s enduring cultural spirit.

As we embark on this journey, from understanding the nuances of its production to savoring its diverse palate, we will not just be exploring a beverage but delving deep into the heart of Japan and its profound love for sake. Join us as we traverse through paddy fields, ancient breweries, and lively izakayas, exploring the mystique and allure of Japan’s liquid heritage.

source: Great Big Story on YouTube

History of Sake in Japan

The history of sake is as intricate and layered as its flavor profile. To understand sake’s place in Japanese culture, we must journey back to its origins, encompassing ancient texts, evolving brewing techniques, and the powerful influences of politics, wars, and societal shifts.

Early Beginnings and Reference in Ancient Texts

The exact origins of sake remain a subject of debate among scholars. However, it is widely believed that rice cultivation and the rudimentary fermentation of rice began in Japan around the 3rd century BC. Over time, these early attempts at fermenting rice evolved into what we recognize as sake today.

One of the earliest references to sake can be found in the “Kojiki” or “Records of Ancient Matters,” which dates back to the 8th century. This oldest extant chronicle in Japan mentions the use of sake in religious ceremonies and offerings to deities. Similarly, the “Nihon Shoki,” another ancient text from the same era, recounts tales of sake being served at imperial courts and its importance in religious rituals. The way these texts revered sake is evidence of its significance in ancient Japanese society.

Evolution of Brewing Methods

The initial brewing methods were likely quite rudimentary. Early sake was probably made using a method called “kuchikami no sake,” where villagers chewed and spat out rice, allowing natural enzymes in saliva to convert rice starches into sugars, which were then fermented.

However, as time passed, brewing techniques underwent refinements. The discovery and utilization of koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) around the 8th and 9th centuries revolutionized sake production. Koji not only eliminated the need for the chewing process but also greatly improved the taste, aroma, and clarity of the resulting drink. This advancement marked the transition from primitive sake brewing to a more sophisticated and standardized production method.

With the establishment of the imperial court in Kyoto during the Heian period (794-1185), sake brewing saw further advancements. Breweries began to employ specific techniques to enhance flavors, leading to the development of several sake varieties.

Influence of Politics, Wars, and Societal Changes

Throughout its history, sake’s production and consumption were heavily influenced by the shifting political and societal landscape of Japan. During the feudal era, samurai lords (daimyō) sponsored and promoted sake production in their domains, recognizing its economic and cultural value. Many of today’s renowned sake breweries can trace their lineage back to this period.

The Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868) brought about relative peace and stability, leading to an urban and cultural boom. The Edo period witnessed the rise of sake as a commercial product, with Edo (modern-day Tokyo) becoming a major hub for sake consumption.

However, wars and political upheavals in Japan’s history often impacted sake production. For instance, during World War II, rice shortages led to the government mandating the addition of pure alcohol and glucose to sake, altering its traditional flavor profile.

In the post-war era, sake faced competition from emerging alcoholic beverages like beer, whiskey, and wine. Yet, it has managed to retain its symbolic and cultural significance. The recent resurgence of interest in traditional practices, coupled with technological innovations, has breathed new life into the sake industry, blending the rich past with a promising future.

The journey of sake through Japan’s history is a vivid tapestry of cultural evolution, resilience, and innovation. From ancient rituals to modern bars, sake’s story is a testament to Japan’s enduring spirit and its undying love for traditions.

source: Paolo fromTOKYO on YouTube

Sake Production

Diving into the world of sake production is akin to entering a realm where art meets science, where age-old traditions blend seamlessly with modern techniques. Producing sake is not merely a process; it’s an intricate ballet of patience, precision, and passion.

At its core, sake brewing is about transforming rice and water into a harmonious elixir through the magic of fermentation. This transformation is guided by the skilled hands of sake brewers, or “toji”, who command an intimate knowledge of the intricate processes involved and have an acute sensitivity to the changing conditions of each brewing batch.

The Importance of Rice

Rice is to sake what grapes are to wine: the essential raw material that defines its character. But it’s not just any rice; sake-specific rice grains are more significant, have a higher starch content, and a more absorbent structure than table rice. This rice, known as “shuzo kotekimai,” provides the essential sugars for fermentation.

Different Varieties and Their Impact on Flavor

Various rice varieties, each with its distinct character, influence the flavor profile of the resulting sake. Some of the most esteemed varieties include:

- Yamada Nishiki: Often dubbed the “king of sake rice,” it’s renowned for producing sake with a clean, full-bodied taste.

- Gohyakumangoku: Produces sake with a light, crisp, and dry profile, popular in regions like Niigata.

- Omachi: One of the oldest sake rice varieties, it imparts a deep, rich, and complex flavor to the drink.

The rice’s outer layer contains proteins and fats, which can introduce unwanted flavors to the sake. Therefore, the degree to which rice is milled or polished, removing this outer layer, is crucial. The more the rice is polished, the purer the starch content and, often, the more refined and delicate the sake flavor.

Water’s Role: Purity and Mineral Content

Water is not just a solvent in sake production; it’s the silent character that can dramatically alter the story of each brew. High-quality water is crucial, and many breweries are strategically located near natural water sources. The water’s mineral content, particularly magnesium and potassium, nourishes the yeast and koji mold, aiding fermentation. Soft water tends to produce smooth and mellow sake, while hard water often results in a more robust and dry sake.

The Role of Koji Mold in Fermentation

Koji mold, scientifically known as Aspergillus oryzae, is the unsung hero of sake production. It facilitates the conversion of rice starches into fermentable sugars. The magic of koji lies in its ability to produce enzymes that break down rice components, paving the way for yeast to work its fermentative wonders.

Brewing Steps:

- Washing, Soaking, and Steaming the Rice: Precision is paramount. Rice is washed to remove bran and then soaked to absorb water. The soaking time varies based on the rice type and its milling rate. Post soaking, rice is steamed, preparing it for koji production and fermentation.

- Koji Production: Steamed rice is spread out in a special room, and koji spores are sprinkled over it. Over a couple of days, under careful monitoring, the koji mold grows on the rice, converting starches to sugars.

- Shubo or Yeast Starter Production: This step is about cultivating a dense population of healthy yeast cells. A mixture of steamed rice, water, koji rice, and yeast is kept in controlled conditions to produce a vigorous yeast starter.

- Multiple Parallel Fermentation: Unlike many alcoholic beverages where sugars are first converted and then fermented, sake undergoes a unique process where saccharification and fermentation happen simultaneously. Over several weeks, the mixture ferments, with brewers adding rice, koji rice, and water in stages.

- Pressing, Filtering, and Pasteurizing: Once fermentation is complete, the liquid is pressed to separate it from the rice solids. This liquid is then filtered to clarify it and is often pasteurized to stabilize it, killing off any active enzymes or microbes.

The culmination of this intricate process is a beverage that captures the essence of its ingredients, the spirit of its makers, and the soul of its homeland. Each sip of sake is a testament to the dedication, craftsmanship, and history that goes into its making.

Classification of Sake

As you delve into the world of sake, you’ll quickly realize that its universe is vast, with myriad classifications that dictate its flavor, aroma, and quality. The classification system is rooted in a combination of traditional methods and modern-day regulations, which hinge on factors such as rice polishing rate, added alcohol, and more.

Factors Determining Different Types

- Rice Polishing Rate: One of the primary determinants of sake’s classification is the extent to which the rice has been polished or milled. The rice polishing rate (known as “seimai buai” in Japanese) indicates what percentage of the original rice grain remains. A higher polishing rate signifies that a larger portion of the outer layer, which contains impurities, has been removed.

- Added Alcohol: Some sake varieties have brewers’ alcohol added to them. This doesn’t necessarily denote a lower quality; instead, the addition of alcohol can enhance certain flavor profiles and aromas.

Common Types and Their Characteristics

- Junmai: Meaning “pure rice”, Junmai sake is made with only rice, water, koji mold, and yeast. There’s no added alcohol in this type. It’s a category that encompasses various grades, based on the rice polishing rate. Junmai sake tends to have a fuller body and a more robust, rice-forward flavor. It pairs well with a variety of dishes due to its rich and complex character.

- Honjozo: In this variety, a small amount of brewers’ alcohol is added to the sake, which often results in a lighter, smoother drink with a slightly fragrant aroma. By regulation, the rice used in Honjozo must have a polishing rate of at least 70%. It’s versatile and can be enjoyed either warmed or chilled.

- Ginjo: A premium sake category, Ginjo is crafted with rice that has a polishing rate of at least 60%. When brewed with added alcohol, it’s labeled as Ginjo. If it’s pure rice without any added alcohol, it’s called Junmai Ginjo. With its fruity and fragrant aroma, often with notes of apple or banana, it’s a favorite among many sake enthusiasts. It’s typically enjoyed chilled to appreciate its nuanced flavors.

- Daiginjo: The pinnacle of premium sake, Daiginjo is made with rice that has been polished to at least 50%, meaning only half or less of the original grain remains. Like Ginjo, there’s both Daiginjo (with added alcohol) and Junmai Daiginjo (without added alcohol). With an even more refined and intricate aroma and flavor profile than Ginjo, it’s often reserved for special occasions. Chilled serving is recommended to savor its delicate notes.

Others

- Nigori: Unlike most sake types that are clear, Nigori is cloudy. This is because it’s coarsely filtered, allowing some rice particles to remain in the liquid. It has a creamy, slightly sweet profile and is often recommended as a dessert sake.

- Umeshu: Not exactly a type of sake but worth mentioning, Umeshu is a Japanese plum wine. It’s made by steeping sour plums in alcohol (often distilled shochu) and sugar, resulting in a sweet and tart beverage. It’s enjoyed as an aperitif or a dessert drink.

To sum up, sake classification, while seemingly intricate, offers enthusiasts a guided pathway to understanding and appreciating the depth and breadth of flavors, aromas, and qualities this traditional Japanese beverage presents. Each classification tells a tale of craftsmanship, ingredients, and brewing decisions, making every sip a journey through history, culture, and art.

Sake Tasting and Appreciation

Sake tasting is more than just sipping a beverage; it’s a rich, multisensory experience. To truly appreciate the depths of sake, one must approach it with a discerning palate, an observant eye, and a curious mind. In this journey of tasting and appreciation, there’s a lot to uncover.

The Art of Tasting: Appearance, Aroma, Taste, and Finish

- Appearance: Before taking that first sip, hold your glass against a white background. The clarity, color, and viscosity of the sake can offer hints about its quality and style. While most sake is clear, variations in color (from pale straw to amber) can indicate aging or specific brewing methods.

- Aroma: Swirl the sake gently in your glass, bringing it to your nose. A well-made sake will release a symphony of fragrances, ranging from fruity notes like apple and pear to floral hints like jasmine, and even savory aromas such as freshly steamed rice. Some premium sakes, especially Ginjo and Daiginjo, are celebrated for their pronounced aromatic profiles.

- Taste: When you sip, let the sake flow over your entire palate. Different parts of the tongue detect different flavors – sweetness at the tip, acidity on the sides, and bitterness at the back. A balanced sake will not overly emphasize any single taste but will present a harmonious blend of flavors.

- Finish: Also known as the aftertaste or “tail,” the finish is the impression sake leaves behind after swallowing. A lingering finish that evolves in flavor is often indicative of a complex and high-quality sake.

Proper Serving Temperature: Chilled, Room Temperature, or Warm

Sake’s flavor profile can transform dramatically based on its serving temperature:

- Chilled (10-15°C): Most premium sakes, especially Ginjo and Daiginjo varieties, are best served chilled to accentuate their delicate flavors and fragrances.

- Room Temperature (20-25°C): Some Junmai sakes, with their full-bodied character, can be enjoyed at room temperature, allowing their complexities to unfold naturally.

- Warm (40-55°C): Heating sake, known as “kanzake,” can elevate the flavors of certain types, especially rich and savory ones. However, overheating can destroy the nuanced flavors, so it’s crucial to warm sake gently and gradually.

Traditional Vessels: Ochoko, Masu, Sakazuki, etc.

- Ochoko: Small cylindrical cups, often ceramic, used for serving sake. Their size is perfect for enjoying sake in small sips, allowing for appreciation of the beverage’s aroma and taste.

- Masu: Originally a wooden box used to measure rice, masu has become a traditional vessel for sake, especially during ceremonies. While it adds a woody aroma, purists often prefer glass or ceramic to prevent interference with sake’s original profile.

- Sakazuki: A flat, ceremonial sake cup, often used in rituals, weddings, and other special occasions.

Sake and Food Pairing Principles

Just like wine, sake can elevate a dining experience when paired correctly:

- Complement or Contrast: A rich, umami-filled sake might complement fatty dishes like pork belly or grilled fish. Conversely, a light, fruity sake can contrast and refresh the palate when paired with spicy foods.

- Regional Pairings: Sake often pairs well with dishes from its region of production. For instance, a sake from Niigata, known for its clean and crisp character, might pair well with the region’s fresh seafood.

- Experiment: While there are guidelines, personal preferences play a significant role. Don’t hesitate to experiment and find pairings that resonate with your palate.

Common Misconceptions about Sake

- Not Just “Rice Wine”: While commonly referred to as rice wine, sake’s production process is closer to beer, where starch is converted into sugar, then fermented into alcohol.

- Not Always Strong: Many believe sake is highly potent. While it generally has a higher alcohol content than wine, it’s typically lower than spirits like whiskey or vodka.

- Not Only for Special Occasions: In Japan, sake is enjoyed regularly, not just on special occasions. Whether it’s a casual dinner or an impromptu gathering, sake finds its place.

Sake is a tapestry of history, craftsmanship, and cultural significance. To truly appreciate it is to embark on a journey that bridges ancient traditions with present-day pleasures, offering a deep, immersive experience in every sip.

Regional Variations

Just as the terroir significantly influences wines, the climate, geography, and local customs of different regions in Japan shape the taste, aroma, and character of their sake. From the snowy landscapes of Niigata to the ancient temples of Kyoto, each region tells a unique story through its sake.

The Influence of Climate and Geography on Sake Flavors

- Climate: The temperature during the brewing process has a profound effect on sake. Cooler temperatures lead to slower fermentation, often resulting in a cleaner, more refined sake. Conversely, warmer regions might produce sake with a bolder, more robust flavor.

- Water Source: Sake is majorly composed of water, making its source pivotal to the final product. Soft water (low in minerals) tends to yield a smooth and mild sake, while hard water (rich in minerals) usually leads to a robust and fuller-bodied sake.

- Rice Varieties: Different regions cultivate different strains of rice. The type of rice, along with its quality, has a profound impact on the sake’s flavor and aroma.

Notable Sake-Producing Regions

- Niigata: Known as the “Snow Country” due to its heavy snowfalls, Niigata boasts a cold climate ideal for sake brewing. The region’s sake is celebrated for its pristine, crisp, and dry profile, often attributed to the soft mountain water and the locally grown rice variety, Gohyakumangoku. Niigata sake is a perfect accompaniment to seafood, reflecting the region’s coastal location.

- Kyoto (Fushimi): With its historical significance as Japan’s ancient capital, Kyoto has long been a hub for sake production. Fushimi, in particular, is renowned for its sake due to its natural spring water known as “Fushimizu.” This soft water yields sake with a smooth, graceful, and elegant character, much like the geishas that the city is famous for.

- Hiroshima: Boasting a relatively warm climate, Hiroshima’s sake is distinct due to its soft water source, which imparts a unique sweetness and depth to the brew. The region is known for its sake’s well-rounded, mild, and slightly fruity profile.

Unique Local Sake Specialties and Festivals

- Nada’s Sake Festival (Kobe): Located in Kobe, the Nada district is one of Japan’s leading sake-producing regions. Every October, the Nada no Kenka Sake Festival celebrates the season’s new brews, with elaborate ceremonies, sake barrel offerings, and lively processions.

- Saijo Sake Festival (Hiroshima): Saijo, a part of Hiroshima, hosts an annual sake festival where visitors can sample sake from numerous breweries, representing various regions. The festive atmosphere, combined with the historic charm of the town’s preserved sake breweries, makes it a must-visit for sake enthusiasts.

- Joys of Sake (Various Regions): This event, held in various cities, is the world’s largest sake-tasting festivity, showcasing hundreds of different sakes. Attendees can indulge in the vast array of flavors, styles, and techniques from across the country.

Each region, with its unique geography, climate, and customs, contributes to Japan’s vibrant sake tapestry. Exploring regional variations not only enhances one’s understanding and appreciation of sake but also offers a profound insight into Japan’s rich culture and traditions.

Modern Innovations and Trends

As centuries-old as sake is, it’s not immune to the winds of change. Today, innovation and adaptation are reshaping the sake world, giving it a fresh, contemporary twist while maintaining reverence for its storied past.

The Emergence of Craft Sake Breweries

- Bridging the Old with the New: Younger generations of brewers, often with experiences outside the sake industry or even outside Japan, are returning to their roots, bringing with them a fresh perspective. They honor time-tested traditions while experimenting with new techniques and flavors.

- Small-batch Productions: Unlike mass-produced sake, craft sake often focuses on quality over quantity. These small-scale breweries prioritize locally sourced ingredients, with an emphasis on sustainability and seasonality. This results in distinctive, often limited-edition brews that reflect the terroir and the brewer’s unique touch.

- Revival of Ancient Methods: Some craft brewers are digging deep into history, reviving ancient brewing techniques that were on the brink of extinction. Such methods can be labor-intensive and time-consuming but yield sake with unparalleled depth and character.

Collaborations with International Brewers

- Cross-cultural Experiments: As sake gains popularity worldwide, collaborations between Japanese sake breweries and international brewers, particularly from the world of beer and wine, are on the rise. These partnerships result in unique brews that merge diverse brewing philosophies, techniques, and flavors.

- Global Sake Education: Many international brewers are undertaking formal sake education in Japan, leading to a global community of certified sake professionals. Their influence helps in the propagation of sake culture and knowledge outside Japan.

- International Sake Competitions: Events such as the International Sake Challenge in Tokyo provide a platform for brewers worldwide to showcase their creations, fostering an environment of mutual respect, learning, and exchange.

New Sake-based Products: Cocktails, Desserts, etc.

- Sake Cocktails: With the global cocktail culture embracing sake, bartenders are concocting innovative mixtures, blending sake with everything from gin to tropical fruits. These cocktails accentuate sake’s subtle flavors while introducing it to a new audience accustomed to mixed drinks.

- Sake-infused Desserts: From sake-flavored ice creams to pastries infused with sake reductions, chefs are weaving the essence of this traditional beverage into modern desserts. Such creations offer a delightful interplay of sweetness, umami, and the distinct notes of sake.

- Sake Skincare: Tapping into sake’s rich amino acid content and fermentation benefits, some companies are introducing sake-based skincare products. These products promise to harness the rejuvenating and moisturizing properties of sake for skin wellness.

- Sake-themed Experiences: Modern establishments, from sake spas offering sake-infused treatments to dedicated sake tasting bars with digital interfaces, are curating experiences that cater to both novices and aficionados.

While sake is deeply rooted in Japanese tradition, it’s evolving in exciting ways that cater to contemporary tastes and global sensibilities. These modern innovations and trends not only ensure sake’s relevance in today’s world but also introduce this ancient beverage to a broader, appreciative audience, ensuring its legacy for generations to come.

Sake in Social and Cultural Context

Sake, often termed ‘the drink of the gods,’ is deeply embedded in the social and cultural fabric of Japan. Beyond its delightful taste and intoxicating effect, sake plays a pivotal role in rituals, inspires artists, and carries profound symbolism within Japanese society.

Role in Ceremonies and Festivals

- New Year (Shogatsu): As the clock strikes midnight on New Year’s Eve, many Japanese households partake in the ritual of toso, drinking a spiced medicinal sake believed to ward off illness for the year. Also, during the first three days of the new year, it’s common to drink otoso, a herb-infused sake, symbolizing purification and the warding off of evil spirits.

- Weddings: Sake holds a sacred spot in traditional Shinto weddings through a ritual known as san-san-kudo. The bride and groom take turns drinking sake from three different-sized cups, symbolizing the union of two individuals and their families. The act represents three human values: happiness, fertility, and longevity.

- Groundbreaking Ceremonies: Before embarking on new constructions or projects, it’s customary to hold a jichinsai or groundbreaking ceremony. Sake is poured on the ground as an offering to the deities, praying for safety and success.

- Harvest Festivals: As a nod to sake’s primary ingredient, rice harvest festivals often incorporate sake. Farmers and communities come together, offering sake to gods in gratitude and seeking blessings for future crops.

Influence on Art and Literature

- Poetry: For centuries, sake has been a muse for many Japanese poets. The transient nature of intoxication mirrors the fleetingness of life, a recurrent theme in Japanese poetry, especially haikus.

- Ukiyo-e: These traditional Japanese woodblock prints often depict scenes from everyday life, including those of sake breweries, drinkers, and festivals. Famous artists like Hiroshige and Hokusai have artworks showcasing sake’s integral role in society.

- Literature: Many classical Japanese tales and modern narratives incorporate sake, either as a central theme or a background element, reflecting its omnipresence in Japanese life. The nuances of brewing, the camaraderie around drinking, and the societal norms linked to sake find their way into literary works, offering readers a glimpse into its cultural significance.

The Symbolism of Sake in Japanese Culture

- Purity: Sake’s clear, unblemished appearance symbolizes purity, which is why it’s frequently used in rituals and offerings. Its association with purification rites in Shintoism also underscores this symbolism.

- Unity: Just as individual rice grains come together to form a harmonious brew, sake symbolizes unity and communal bonds. Sharing sake from the same bottle or flask strengthens interpersonal ties, be it among family, friends, or even strangers.

- Blessings & Gratitude: Sake, derived from rice, represents Japan’s agricultural heritage. Drinking sake is not just a sensory pleasure but also an act of gratitude, acknowledging nature’s bounty and human effort.

- Transition & Renewal: Sake rituals in ceremonies often signify transitions, be it the change of years, union in marriage, or the commencement of new ventures. As such, sake becomes a symbol of renewal and fresh beginnings.

In weaving through the tapestry of Japan’s history, folklore, art, and everyday life, sake stands out not just as a beverage but as a repository of cultural values, beliefs, and traditions. Its enduring presence in various facets of Japanese life underscores its significance, not just to the palate but to the soul of Japan.

Sake Tourism in Japan

Over the past few decades, as the global fascination with Japanese culture has surged, so has interest in sake. Japan has astutely combined this global curiosity with its rich sake heritage, giving birth to a burgeoning industry: sake tourism. This form of tourism not only educates and entertains visitors but also revives local economies and fosters a deep appreciation for this time-honored beverage.

Sake Breweries as Tourist Destinations

- Historical Charm: Many of the sake breweries in Japan have histories that span several centuries. These establishments, often still housed in their original wooden structures, offer a glimpse into the past. With their rustic ambiance, cobblestone paths, and aged cedar walls, visitors are transported to a bygone era.

- Educational Experiences: Breweries typically offer guided tours where visitors can witness the intricate process of sake-making firsthand. From the washing of the rice to the magical transformation brought about by koji mold, it’s a journey of discovery. Along the way, artisans share anecdotes, secrets, and the philosophy behind their craft.

- Hands-on Workshops: Some breweries offer interactive experiences where tourists can participate in various stages of brewing, be it rice planting, harvesting, or even bottling. Such immersive experiences deepen the connection between the drinker and the drink.

Guided Sake Tasting Tours

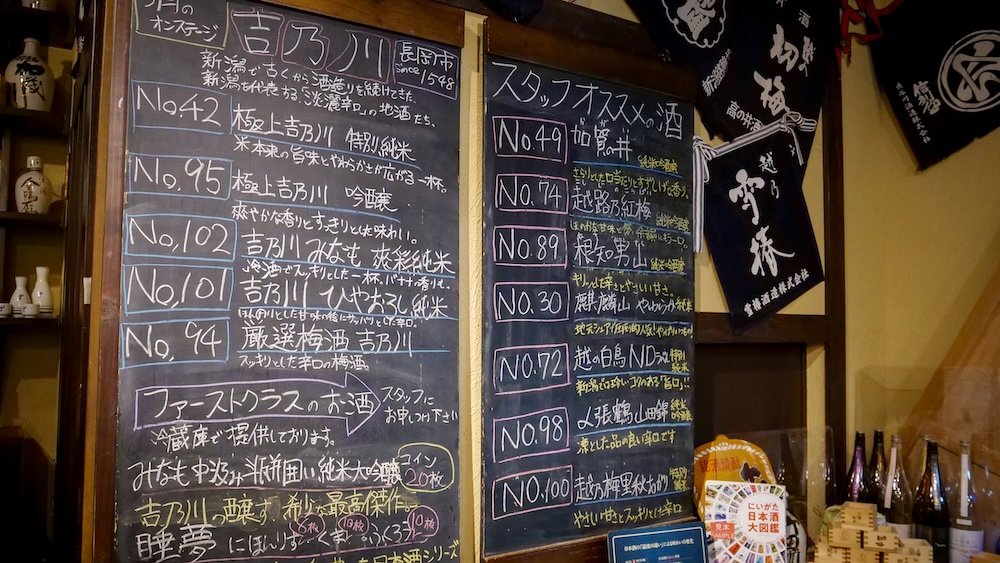

- Structured Tastings: These are sessions where visitors are introduced to different types and grades of sake. Under the guidance of sake sommeliers, one learns to discern the nuanced flavors, aromas, and textures of various brews.

- Food Pairings: Understanding sake in isolation is one thing, but recognizing how it complements food is a revelation. Several tours offer curated meals, where each dish is paired with a sake that accentuates its flavors.

- Regional Sake Trails: Various regions in Japan, renowned for their sake, have established trails that tourists can follow. For instance, the Niigata Sake Trail or the Kyoto Fushimi Sake District allows visitors to hop from one brewery to another, each offering its unique taste and story.

Famous Sake Festivals and Events for Travelers

- Sake no Jin (Niigata): One of the largest sake festivals in Japan, Sake no Jin brings together over 90 breweries from Niigata Prefecture. Tourists can sample from a vast array of sakes, attend seminars, and enjoy live performances.

- Saijo Sake Festival (Hiroshima): As mentioned earlier, this festival in Hiroshima’s Saijo district is a haven for sake enthusiasts. The streets come alive with stalls, music, and dance, all celebrating the beloved beverage.

- Nihonshu no Hi (National Sake Day): Held every October 1st, this day marks the official start of the sake brewing season. Various events, discounts, and promotions are organized throughout the country, making it a perfect time for tourists to immerse themselves in sake culture.

- Kanazawa Sake and Seafood Soiree (Ishikawa): Held in the picturesque city of Kanazawa, this event marries the region’s fresh seafood with its premium sake, offering a gastronomic delight to visitors.

Sake tourism in Japan is more than just about tasting a beverage. It’s a holistic experience that entwines the senses, intellect, and soul. Visitors come away not just with a palate educated in the subtleties of sake but with memories, stories, and a profound appreciation for the artisans and the culture that births this exquisite drink.

Planning Your Sake Adventures in Japan

If you love the idea of sake but feel a bit lost when you’re actually handed a menu, you’re not alone. The good news is that Japan makes it very easy to turn curiosity into real-world experiences – from standing bars in back alleys to sleepy countryside breweries where the toji still stirs tanks by hand.

You don’t need to become an expert overnight. You just need a rough game plan.

What Kind of Sake Traveller Are You?

Here’s a quick way to frame your trip before you start plugging things into an itinerary:

| Traveller Type | Main Goal | Best Base/Region to Prioritize | Typical Time Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curious Beginner | Try a few styles, not get overwhelmed | Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka | 1–2 evenings |

| Food + Sake Pairing Lover | Izakaya nights and tasting sets | Tokyo, Kyoto, Kanazawa | 2–4 evenings |

| Brewery Hunter | See how it’s made, meet makers | Niigata, Hiroshima (Saijo), Kobe | 1–3 full days per region |

| Deep Dive Enthusiast | Region-by-region exploration | Niigata, Akita, Yamagata, Hyogo | 1+ weeks |

| Winter Onsen + Sake Fan | Snow, hot springs, hot sake | Niigata, Nagano, Tohoku | Long weekend or more |

Once you know roughly where you fall, you can start picking concrete places and experiences rather than just “drink more sake.”

Where to Base Yourself for Sake

You’ll find sake everywhere in Japan, but a few places make it especially easy to dive in without too much planning.

Tokyo: Gentle Introduction, Endless Choice

Tokyo is ideal if you want to taste widely without going anywhere rural.

- Seek out specialty sake bars in neighbourhoods like Shinjuku, Shibuya, Kanda, or Ebisu. Many offer tasting flights with English menus.

- Department stores often have basement liquor sections with dozens (or hundreds) of bottles and staff who love to talk about their favourites.

- Look for small tachinomi (standing bars) near stations. They’re casual, cheap, and great for people-watching.

Tokyo is less about breweries and more about breadth – you can drink Niigata, Hiroshima, Akita, and Kyushu in a single evening if you want.

Kyoto & Fushimi: History in a Cup

Kyoto brings together temples, old streets, and elegant sake. The Fushimi district is particularly known for soft water and smooth, gentle brews.

- Spend half a day in Fushimi, visiting breweries that offer small tastings and simple tours.

- Combine it with a visit to Fushimi Inari Shrine and make it a walking day: shrine in the morning, sake town in the afternoon, izakaya in the evening.

- Expect mellower sake that pairs nicely with Kyoto-style kaiseki or delicate tofu dishes.

Kobe & Nada: Powerhouse Brewing District

Between Kobe and Nishinomiya you’ll find the Nada area, one of the country’s great sake powerhouses.

- Several breweries maintain museum-style visitor centers, with old tools, displays, and tasting corners.

- You can walk or hop trains between multiple breweries in one afternoon.

- Sake here often has a slightly firmer, drier profile, great with grilled fish or salty bar snacks.

Niigata: Snow Country and Super-Clean Sake

If you want to connect rice paddies, winter scenes, and sake in one go, Niigata is a dream.

- Expect crisp, dry, “tanrei” (clean) styles, many using the local Gohyakumangoku rice.

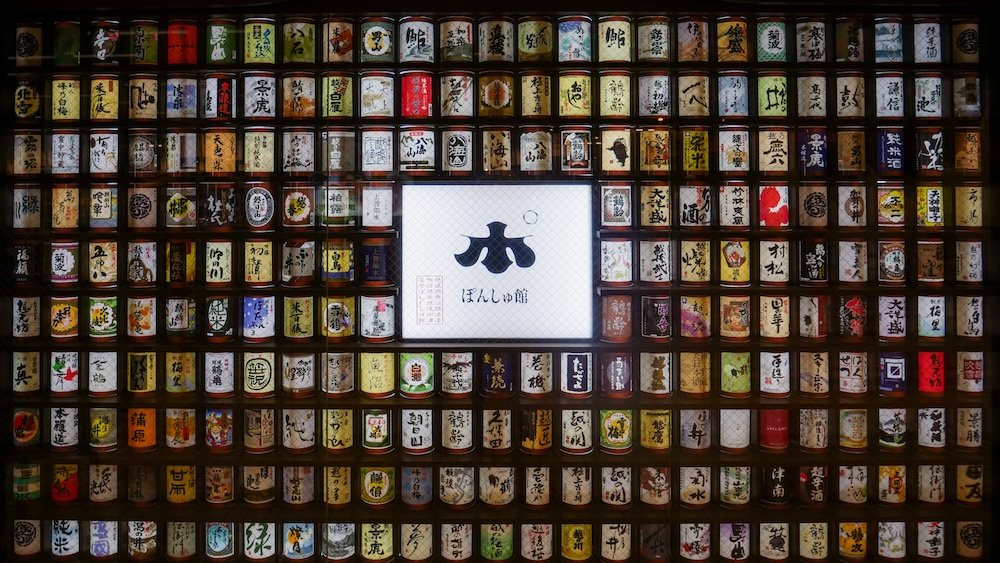

- In places like Niigata City or Yuzawa, you’ll find tasting stations where you can sample multiple labels with prepaid tokens.

- In winter, combine skiing or onsen with hot sake in a ryokan. It doesn’t get much cozier than that.

Hiroshima & Saijo: Soft Water, Gentle Sake

Hiroshima’s soft water gives many of its sakes a rounded, slightly sweet character.

- The Saijo area has a walkable street lined with traditional breweries, white walls, and brick chimneys.

- Plan a brewery-hopping afternoon and finish at a local izakaya where staff are happy to recommend pairings.

How to Read a Sake Menu Without Freezing

Japanese sake lists can look intimidating at first glance, but you don’t need to decode every character to order well. A few key words go a long way.

Key Terms You’ll See Again and Again

| Term | Rough Meaning | What You Can Expect in the Glass |

|---|---|---|

| Junmai | “Pure rice” (no added alcohol) | Fuller, rice-forward, sometimes richer |

| Honjozo | Small amount of added alcohol | Cleaner, lighter, very drinkable |

| Ginjo | Higher-polished rice | More fragrant, fruity, often served chilled |

| Daiginjo | Very highly polished rice | Elegant, delicate, special-occasion territory |

| Nigori | Cloudy, coarsely filtered | Creamy, sometimes sweet, good as dessert or fun sip |

| Nama | Unpasteurized | Fresh, lively, often needs refrigeration |

| Karakuchi | “Dry” | Less sweetness, leaner profile |

| Amakuchi | “Sweet” | Noticeably sweeter, softer on the palate |

If you remember just Junmai, Ginjo, Daiginjo, Nigori, and karakuchi, you can already have a good conversation with staff.

Simple Ordering Strategy

If you feel stuck, try this approach:

- Start with: “Junmai Ginjo, karakuchi, one glass please” – you’ll usually get a clean, balanced sake with good aroma.

- Ask the staff: “Osusume wa arimasu ka?” (Do you have a recommendation?) and mention whether you like dry or sweet.

- Order a tasting set if available. Three small pours teach you more than one big glass.

You don’t need perfect pronunciation. Sake people are usually thrilled you’re trying.

Sake Experiences to Try in Japan

You can build an entire trip around sake, or just sprinkle these experiences throughout a broader itinerary.

Standing Sake Bars

These tiny spots are everywhere once you start noticing them.

- No reservations, often just a counter and a few barrels.

- Great if you’re solo or as a pre-dinner stop.

- Prices are usually friendly, and you can try one or two glasses without any pressure to linger.

Izakaya Nights

Izakaya are where sake really comes to life alongside food.

- Order one carafe (tokkuri) of sake and a few small plates: grilled mackerel, karaage, tofu, pickles.

- Mix styles and temperatures: maybe a room-temperature Junmai first, then a chilled Ginjo.

- Don’t be afraid to say, “sake that goes well with grilled fish” and let the staff choose.

Brewery Tours and Tasting Rooms

In sake towns you’ll often find breweries with visitor areas.

Typical flow looks like this:

- Short orientation or video about the history of the brewery.

- A walk past fermentation tanks or polished rice.

- Tasting corner where you try a few labels, sometimes with simple snacks.

Some places require advance reservations, especially in busy seasons, so check ahead if there’s a specific brewery you’re excited about.

Department Store and Train Station Tastings

Japan loves to hide surprises in everyday places.

- Big-city department stores often have weekend or seasonal tastings on their liquor floors.

- Some train stations in sake-heavy regions have coin-operated tasting machines where you load money onto a card and pour tiny samples from automated dispensers. It feels a bit sci-fi and is a fun way to experiment.

Budgeting for Sake on Your Trip

You don’t need a luxury budget to enjoy sake in Japan. It helps to know what things roughly cost so you don’t get caught off guard.

What You’ll Typically Pay

| Experience | Rough Price Range (per person) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Single glass in an izakaya | Low to mid range | Larger pours than tasting sets |

| Tasting flight (3–5 small pours) | Low–mid range | Great value, especially in sake bars |

| Brewery tour + tasting | Free to mid-range | Some charge a small fee, others absorb it as PR |

| Bottle from convenience store | Very low–mid range | Everyday table sake, good for casual evenings |

| Premium bottle from specialty shop | Mid to high | Junmai Daiginjo and limited releases |

Prices vary wildly at the top end, but for most travellers, sake is surprisingly affordable compared to wine in many countries.

Where to Save and Where to Splurge

- Save: Daily drinks in izakaya, convenience store experiments, basic warm Junmai with oden or hotpot.

- Splurge: A really good bottle from a favourite brewery, a tasting set of rare labels, or one special meal where each course is paired with sake.

Sample Sake-Focused Itineraries

You can do a lot with just a few well-placed sake stops. Here are some easy templates you can adapt.

7–10 Day Classic Route with Sake Highlights

Tokyo → Kyoto → Osaka/Kobe

Tokyo (3–4 nights)

- One evening in a sake specialty bar, tasting across different regions.

- Another evening in an izakaya-heavy neighbourhood (like Shinjuku or Kanda), pairing sake with yakitori and grilled fish.

Kyoto (3 nights)

- Half day in Fushimi: brewery visits, casual tastings, maybe a simple lunch by the river.

- One slow evening with Kyo-style kaiseki or obanzai, sipping a soft, gentle Kyoto sake.

Osaka/Kobe (2–3 nights)

- Day trip to Nada: walk between breweries, museum-style visits, souvenir shopping.

- Back in Osaka, finish with a street-food dinner (takoyaki, okonomiyaki) and a bold local sake to cut through the richness.

Long Weekend in Niigata: Snow, Onsen, and Sake

Perfect if you want a compact, memorable sake experience away from Tokyo.

- Day 1: Arrive in Niigata City, drop bags, sake tasting in town, seafood dinner.

- Day 2: Head to a ski resort or onsen town (like Yuzawa area in winter), enjoy hot springs by day and hot sake at night.

- Day 3: Quick stop at a sake museum or shop before heading back.

In winter, snow outside + rotemburo + steaming cup of Junmai = a moment that sticks with you.

Etiquette, Tips, and Common Mistakes

Sake culture is rooted in hospitality and politeness, but you don’t need to be perfect. A little awareness goes a long way.

Pouring and “Kampai”

- Try not to pour for yourself first in a group. Instead, pour for others, and they’ll pour for you.

- Hold your cup with two hands when someone is pouring – it shows appreciation.

- Japanese “cheers” is “Kampai!” – say it with a smile and you’re already halfway there.

How to Show You’ve Had Enough

If you’re done, just leave your cup more than half full and stop cradling it. Most staff will take the hint. You can also gently say, “kore de daijoubu desu” (I’m fine now).

Don’t Rush the Temperature

A lot of visitors assume sake is always hot. It’s not.

- Premium Ginjo and Daiginjo are usually best chilled or slightly cool.

- Fuller Junmai can be room temperature or warm, especially on a cold night.

- If you’re curious, ask to try the same sake at two temperatures – it’s a fun little experiment.

Bringing Sake Home

If you fall in love with a particular brewery or bottle, chances are you’ll want to bring a piece of Japan back with you.

Bottle Sizes and Practicalities

- Common sizes are 720 ml and 1.8 L (the big isshobin). The large ones are impressive but heavy in luggage.

- Many shops sell smaller 300 ml bottles – perfect for gifts or for travellers with weight limits.

A Few Things to Keep in Mind

- Nama sake (unpasteurized) needs refrigeration and is generally not ideal for long flights unless you know you can keep it cold.

- Wrap bottles in clothes or bubble wrap inside your checked luggage to avoid heartbreak at baggage claim.

- Duty-free at airports often has curated selections from multiple regions, which can be handy if you didn’t buy anything earlier or want last-minute gifts.

Drinking Sake Safely and Comfortably

Sake is smooth. Suave. That can be dangerous. It creeps up on you.

- Alternate glasses of sake with water. Many izakaya will happily bring you tap water if you ask.

- Make sure you eat while you drink – Japanese drinking culture assumes food on the table, not empty stomachs.

- Keep an eye on the last train time if you’re staying in bigger cities; taxis after midnight add up quickly.

- If you’re visiting breweries in rural areas, don’t drive yourself. Use trains, buses, taxis, or stay overnight nearby.

Essential Questions About Exploring Japan’s Sake Culture: Practical Answers & Traveler Tips

Is sake actually strong, and how much can I safely drink in one night in Japan?

Generally, yes. Sake sits in roughly the same strength zone as wine, but it’s incredibly smooth, which is why it creeps up on people. One full glass can feel milder in the moment than a cocktail, but it still adds up over an evening.

If you’re new to sake, I’d treat one generous glass or a couple of small cups over a relaxed dinner as “taking it easy”, especially if you’re jet-lagged or not used to drinking. Go slowly, sip rather than knock it back, and eat while you drink.

If you’re doing tasting flights, think of them as equivalent to a few normal drinks spread out. Give yourself time between pours, drink water, and don’t schedule an early, jam-packed sightseeing day right after a big sake night.

When is the best time of year to visit Japan if I’m interested in sake culture and brewery visits?

It depends. You can enjoy sake year-round, but the feel of the trip changes with the seasons.

Winter is fantastic if you like the idea of snow, steaming onsen, and hot sake at night. Many breweries are actively brewing in the colder months, so towns in regions like Niigata or northern Honshu have a really atmospheric vibe.

Autumn is another sweet spot: crisp air, changing leaves, and plenty of food-focused events where sake shows up alongside seasonal dishes. Spring works well too if you want to combine cherry blossoms with izakaya nights, but it’s also peak tourism season, so things book up earlier.

Summer tends to be hot and humid in much of Japan. You’ll still find plenty of chilled sake, just be ready for sticky evenings and factor in more breaks.

How many days should I plan in my itinerary just for sake-related experiences?

Honestly, you can go as deep as you want. If you’re a casual drinker who just wants to get comfortable reading a menu and try a few styles, one or two evenings in Tokyo or Kyoto is plenty.

If you’re a curious enthusiast, I’d carve out at least two or three days where sake is the main theme: a brewery town day, an izakaya-heavy night, and maybe a tasting-focused evening in a specialty bar.

Hardcore fans can easily spend a week bouncing between regions like Niigata, Nada (near Kobe), Hiroshima, and a big city base. The nice thing is that sake layers very well onto a normal Japan itinerary – you don’t need a totally separate “sake trip”; you just choose a few strategic stops.

Which Japanese cities or regions make the best base if I want to combine sake with general sightseeing?

Absolutely. A few places make sake exploration almost effortless while still ticking the classic sightseeing boxes.

Tokyo is your all-rounder: endless sake bars, department store tastings, and bottles from every corner of the country, all wrapped into one mega-city. It’s ideal if you want variety more than brewery visits.

Kyoto is great if you like the idea of temple-hopping by day and sipping gentle, soft local sake at night. Add in a half-day in the Fushimi district and you get history, waterways, and breweries in one go.

For a more brewery-focused base, places around Kobe, Hiroshima (especially Saijo), and Niigata work well. They give you easy access to multiple breweries plus nearby onsen, coastal scenery, or city life, depending on which you choose.

Do I need to speak Japanese to enjoy sake bars, izakaya, and brewery tours?

Nope. You can get a long way with smiles, a few key words, and pointing.

In bigger cities, plenty of bars and izakaya have at least one staff member who can manage basic English, and some places have English or picture menus. Even when they don’t, staff are usually thrilled you’re interested in sake and will happily recommend something if you just say “recommendation, please” and mime drinking.

Learning a handful of words helps a lot: “karakuchi” (dry), “amakuchi” (sweet), “osusume wa?” (what do you recommend?), and “kampai!” (cheers). If you’re nervous, start with specialty sake bars that advertise English-friendly service or join a small-group tasting tour for your first night.

What kind of budget should I expect for sake tastings, bar nights, and brewery visits?

It’s usually more affordable than people expect. A single glass of decent sake in an everyday izakaya often costs about what you’d pay for a beer or simple cocktail back home. Tasting flights are usually good value because you get to compare several styles without committing to full glasses.

Standing bars tend to be lighter on the wallet, while premium hotel bars and very fancy restaurants are where things jump up. Brewery tastings can range from free tiny samples to paid flights, but the price is rarely outrageous.

If you’re worried about costs, set a rough “sake budget” per day – enough for one or two drinks in the evening – and then choose one or two special splurge experiences, like a high-end pairing dinner or a bottle from a brewery you fall in love with.

Is it okay to visit sake spots if I’m traveling with kids or I don’t drink much alcohol?

Absolutely. You don’t have to be a heavy drinker (or drink at all) to enjoy the culture around sake.

Some breweries welcome families on daytime tours as long as kids aren’t tasting alcohol. You’ll want to be respectful of safety rules and keep little ones close around equipment, but it can be a genuinely interesting cultural stop rather than just a “bar visit.”

If you don’t drink much, focus on experiences where sake is part of a bigger picture: dinner in a traditional restaurant, an onsen ryokan where you try a small cup with a long meal, or a guided tour where you can sip tiny amounts and spit or skip pours when you’ve had enough. There are also non-alcoholic options in many places, like teas, soft drinks, or sweet low-alcohol amazake.

What basic etiquette should I know for ordering, pouring, and saying “kampai” with sake?

Relax – it’s not as scary as it looks. A little effort goes a long way.

In a group, it’s considered polite to pour for others rather than topping up your own glass first. When someone pours for you, hold your cup with one or two hands and give a small nod or “arigatou.”

Wait for everyone to have a drink before you start, lift your glass, and say “kampai!” with eye contact and a smile. You don’t need to clink hard; a gentle touch is fine. After that, just drink at your own pace.

If you’re not comfortable drinking more, leave your cup fairly full and stop cradling it. Most people will read that as a sign you’re done and will not press you to keep going.

Is going out for sake at night in Japan safe, and are there any areas or situations I should be cautious about?

Generally, yes. Japan is one of the easier countries in the world to go out at night, wander between bars, and hop on trains back to your hotel without feeling too stressed. Streets around stations are often busy late into the evening, especially in big cities.

That said, basic common sense still applies. I avoid very pushy “street touts” who try to drag me into upstairs bars in nightlife districts and stick instead to places that look busy with locals or have clear menus displayed. I also keep an eye on my drink like I would anywhere else, and I don’t leave belongings unattended.

If you’re solo, especially if you’re drinking more than usual, it’s smart to bookmark your accommodation on your phone, know your last train time, and have a backup taxi or rideshare option.

Can I drive or cycle after “just one” glass of sake in Japan?

Honestly, I treat it as a firm no. Japan takes drinking and driving very seriously, and even small amounts of alcohol can get you into trouble if something happens on the road.

If you’re planning to drink, plan not to drive – that includes rental cars, motorbikes, and even bicycles in many places. Japan has excellent trains, subways, and taxis, and in smaller towns there are usually local buses or walkable routes between bars and your accommodation.

The easiest rule is: the designated driver drinks tea, soft drinks, or non-alcoholic options only, and everyone else can relax and enjoy their sake without doing mental math about “how much is too much.”

What should I pack if I’m planning a winter onsen-and-sake trip to snowier regions?

Cozy. Think layers. Winter in sake-heavy snow regions can be cold, windy, and very snowy, especially at night.

I’d bring a warm coat, thermal base layers, thick socks, and shoes or boots with decent grip for icy streets. A compact umbrella or waterproof hood is handy for those wet snow days when you’re walking between station, ryokan, and brewery.

For onsen, pack a small bag for towels, a change of clothes, and maybe some slip-on sandals for walking between indoor and outdoor areas. After soaking, you’ll really appreciate having comfortable loungewear to throw on before you sit down with a hot cup of sake in the evening.

How do I choose a good bottle of sake to bring home when I can’t read the label?

Start simple. In a shop, pick one bottle that you’ve already tried on the trip and loved – maybe from a brewery visit, a tasting bar, or a restaurant where you snapped a photo of the label. That way you’re buying a memory, not just a random bottle.

If everything is new, look for clearly marked categories like “Junmai Ginjo” or “Junmai Daiginjo” if you enjoyed fruity, fragrant sakes, or “Junmai” if you preferred richer, more rice-forward styles. Many shops will group bottles by sweetness or dryness, sometimes with simple number scales.

When in doubt, ask staff for “something easy to drink” or “something to pair with seafood/back home food you like.” Most shop staff love the chance to recommend a favourite bottle, even with very simple English and lots of pointing.

I love the idea of sake but I get hangovers easily – any tips for enjoying it without suffering the next day?

Yes. Slow down and add structure.

First, eat. Sake on an empty stomach is a fast track to feeling rough the next morning, so align your pours with food: salty snacks, grilled fish, rice dishes, or izakaya plates. Second, match every glass of sake with water – either between drinks or right alongside. Many bars will happily keep bringing you water if you ask.

I also like to choose one or two good sakes to enjoy slowly instead of sampling absolutely everything in one night. If you know you’re sensitive, plan a lighter sightseeing schedule the next morning, maybe with a late start and lots of outdoor wandering rather than a rigid museum schedule.

Is sake gluten-free and suitable if I’m vegetarian, vegan, or have other dietary restrictions?

Often, but not always. Traditional sake is made from rice, water, yeast, and koji mold, which are all naturally gluten-free and plant-based. The tricky part is that some breweries may use small amounts of additional ingredients or equipment that introduce potential cross-contamination.

If you’re extremely sensitive to gluten, many people feel more comfortable sticking to “Junmai” styles (which focus purely on rice) and asking the brewery or bar whether anything containing wheat or barley is used in the process. Labels and staff won’t always have detailed allergen information, so you may want to stay cautious.

For vegetarians and vegans, the drink itself is usually less of an issue than the food that comes with it. Izakaya menus often lean heavily on fish, meat, and dashi-based broths, so it’s worth learning a few basic Japanese phrases for your dietary needs or seeking out places that clearly label vegetarian and vegan options before diving into a sake-heavy meal.

Conclusion: Sake in Japan

The story of sake is, in many ways, the story of Japan — a harmonious blend of tradition and innovation, nature’s bounty and human endeavor, spiritual significance and worldly enjoyment.

The Enduring Appeal and Cultural Significance of Sake

- Mirror to History: Every sip of sake is a journey back in time, echoing tales of ancient emperors, resourceful artisans, and villages that centered their lives around rice cultivation. It’s remarkable how this beverage has weathered societal changes, political upheavals, and shifting consumer tastes, yet remains a cherished part of Japan’s identity.

- Craftsmanship and Artistry: The meticulous craftsmanship behind sake production stands as a testament to Japan’s broader cultural ethos: a relentless pursuit of perfection, whether in sword-making, tea ceremonies, or pottery. Sake brewing is less of an industry and more of an art, handed down through generations, each adding their own touch but respecting the core essence.

- Spiritual Elixir: Beyond its worldly pleasures, sake holds a sacred place in the Japanese spiritual landscape. Used in Shinto rituals, festivals, and ceremonies, it bridges the human realm with the divine, serving as an offering, a purifier, and a medium to invoke blessings.

Encouragement to Explore and Appreciate Japan’s Sake Heritage

- A Universal Language: While sake is deeply Japanese, its appeal is universal. The flavors, aromas, and the warm embrace of a well-brewed sake glass can be appreciated by anyone, irrespective of their cultural or geographical origins. And in this appreciation lies a deeper connection to Japan and its people.

- Embarking on a Sake Journey: For those yet to delve into the world of sake, there’s a rich tapestry waiting to be unraveled. Visit a local sake brewery, attend a sake-tasting seminar, or simply share a bottle with friends. Each experience will offer a new insight, a new story.

- Preservation through Participation: As global citizens, our engagement with and appreciation for sake can play a role in preserving this ancient craft. By visiting sake regions, supporting artisanal breweries, and advocating for its global recognition, we contribute to the legacy of sake, ensuring it thrives for future generations.

In the delicate dance of water, rice, yeast, and koji mold, Japan has found an expression of its soul. It’s an expression that invites participation, urging both the uninitiated and the connoisseur to partake in its joys. As we raise our glasses, filled with the shimmering liquid, we aren’t just toasting to a drink, but to centuries of tradition, culture, and the indomitable spirit of Japan. Kampai!