Fernie is where we kicked off our BC road trip—and honestly, it felt like coming home in the best possible way. We’re living in southern Alberta these days, so crossing back over into British Columbia always flips a switch for me. The air changes. The mountains feel familiar. And suddenly we’re back in that classic BC rhythm: walkable downtown, wild scenery five minutes away, and a small-town pace.

We were here as a little trio—me (Nomadic Samuel), Audrey Bergner (That Backpacker), and our baby daughter, Aurelia—who was absolutely thriving the whole time. Flowers, butterflies, stroller rides, baby-backpack hikes… she was basically the happiest tiny traveler in the Rockies. And that “family-friendly and outdoorsy” vibe is something you feel immediately in Fernie: it’s charming, laid-back, and surprisingly easy to explore on foot.

But Fernie also hit me on a deeper level, because I grew up in a small town in BC—Gold River on Vancouver Island—where you learn early that small towns don’t survive on vibes alone. They survive because people get resilient. They adapt. They reinvent. When the old economic engine sputters, you either find a new identity or you fade out. So walking Fernie’s historic core, it wasn’t hard to imagine the cycles this town has lived through—and the grit it took to keep going.

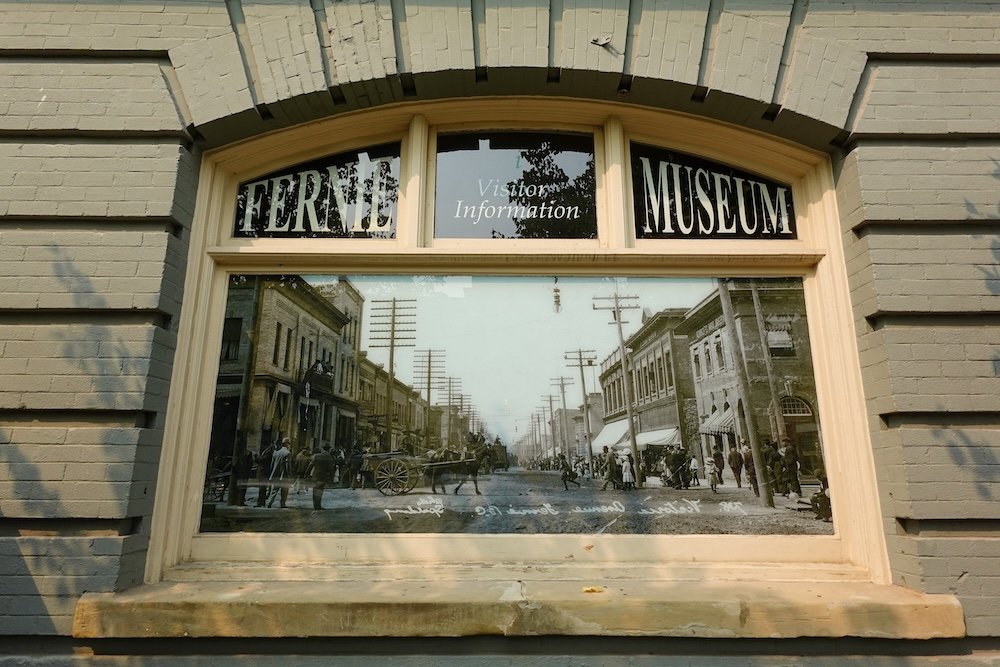

That’s why the Fernie Museum felt like such a must-do right out of the gate. It’s the kind of place that gives you instant context: origins, tragedy, resilience, reinvention. You walk in thinking you’re visiting a cute mountain town, and you walk out realizing you’re standing in a community that has rebuilt itself—more than once—and somehow turned that hard-earned history into the Fernie you get to experience today as a visitor.

Quick history snapshot

- Fernie sits in the traditional territory of the Ktunaxa Nation, whose homeland includes the Elk Valley and surrounding Rockies.

- The modern town took off because of coal, with mines starting up in 1897 and the Canadian Pacific Railway arriving in 1898—suddenly Fernie could ship what it dug up.

- Fernie’s early decades were marked by terrifying risk: a major coal mine explosion in 1902 became one of Canada’s deadliest mining disasters.

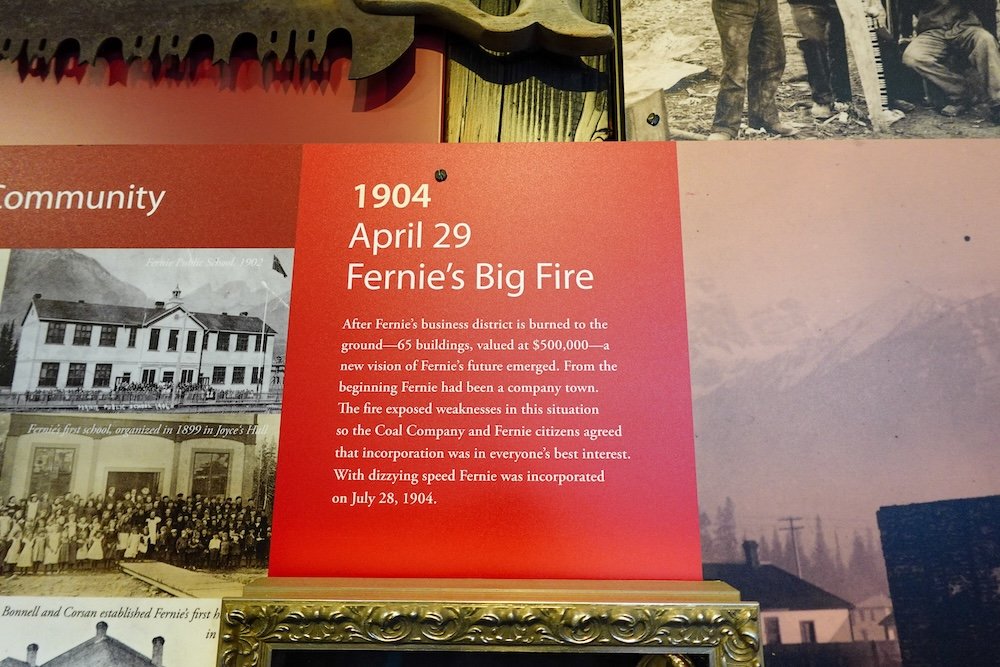

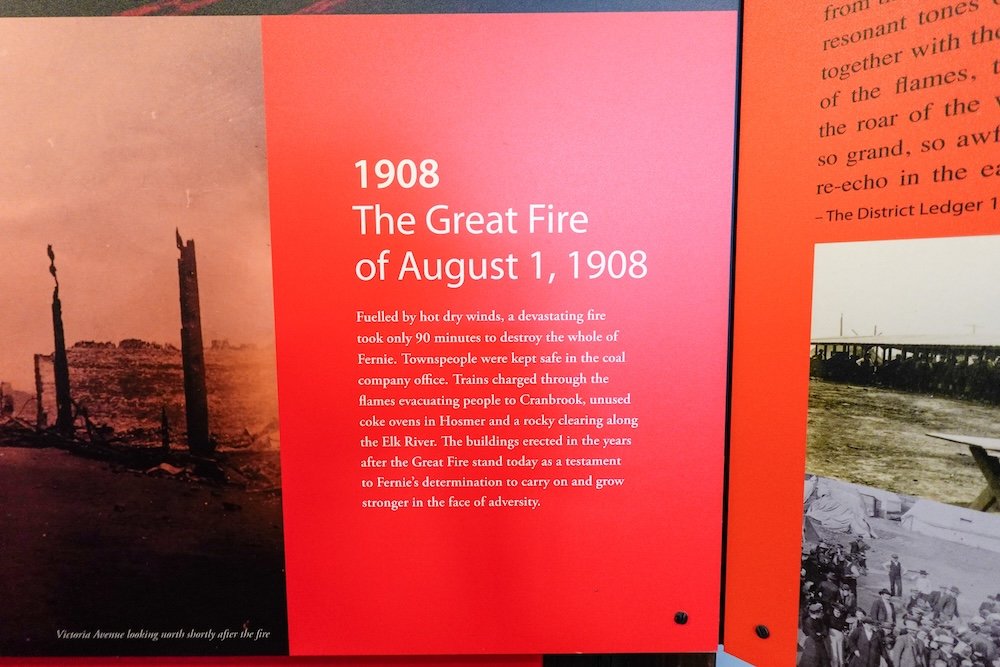

- Two massive fires reshaped everything: a 1904 fire and the Great Fire of August 1, 1908, which destroyed much of the community in under 90 minutes—and pushed Fernie to rebuild its downtown core in brick and stone.

- A lot of Fernie’s most photogenic “Old Town” look exists because of that rebuilding era: heritage buildings, Romanesque arches, and chateau-style civic architecture.

- Fernie’s story also includes harder chapters travelers often miss: First World War internment operations in the region (including Morrissey) and the long tail of discrimination faced by immigrant communities.

- The economy later diversified: coal remained central, but locals helped launch ski tourism—Fernie Snow Valley opened in 1962, and the community even pursued a 1968 Winter Olympics bid that helped legitimize the dream.

- We felt the “then + now” contrast immediately: one minute we’re eating burritos and bagels downtown, the next we’re standing at a museum exhibit about fires, mine disasters, and reinvention—then hiking to a waterfall with the baby in a backpack.

Timeline at a glance

| Era / Year | What happened | Why it matters today | Where you can see it |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thousands of years to present | Ktunaxa Nation homeland includes the Elk Valley; living culture continues | The “first chapter” of Fernie isn’t 1898—it’s far older, and still ongoing | Interpretive materials + regional cultural context; approach with respect |

| 1897–1898 | Coal mining begins (1897); CPR arrives (1898) and the town takes shape | Fernie becomes a true resource town with rail-powered growth | Historic downtown grid; rail corridor; museum context |

| 1902 | Coal mine explosion kills many miners (often cited as 128) | The tragedy is foundational to Fernie’s identity and labour history | Fernie Museum exhibits; community remembrance |

| 1904 | Fire destroys much of the commercial district | Leads into incorporation + the push for better civic services | Downtown “heritage core” story begins here |

| Aug 1, 1908 | Great Fire devastates Fernie in < 90 minutes | Rebuild era creates the brick-and-stone downtown you walk today | Brick façades, soot traces, heritage walk stops |

| 1909–1912 | Signature civic/religious buildings rise (courthouse, churches, banks) | Fernie’s architecture becomes unusually grand for a “small” town | Courthouse; Holy Family Church; bank buildings |

| 1914–1920 (regional) | Internment operations affect the area; Morrissey connected to the story | A reminder that “wartime Canada” included imprisonment and forced labour | WWI Internment Memorial; Morrissey remembrance |

| 1923 | Home Bank failure hits Fernie depositors hard | Economic shock still echoed in local memory | Home Bank building (now Fernie Museum) |

| 1962–1963 | Fernie Snow Valley opens (Jan 10, 1962); ski momentum grows | Tourism becomes a second pillar and eventually a defining identity | Fernie Alpine Resort’s origin story |

| 1997–1998 | Resort purchased/renamed; major expansions | Fernie becomes internationally known for skiing + four-season recreation | Fernie Alpine Resort base + bowls legacy |

Before “modern Fernie”

Fernie isn’t an “accidental” town. Geography stacked the deck.

This corner of southeastern British Columbia sits in the Rocky Mountains, shaped by valleys and passes that make movement—and later transport corridors—possible. Long before a railway schedule mattered, this landscape mattered to the Ktunaxa Nation as part of their homeland, with deep time connections that continue today.

By the late 1800s, what drew outside industrial attention was coal. Not “a little seam,” but the kind of resource that changes maps: investment, labour migration, company towns, rail lines, and a new downtown grid that (to this day) makes Fernie feel walkable and surprisingly “city-like” for its size. Fernie’s own historical summaries tie the town’s existence directly to coal start-up in 1897 and the CPR’s arrival in 1898.

The turning points that shaped Fernie

Coal makes a town (1897–1898)

Fernie takes its name from William Fernie; local histories also spotlight Colonel James Baker as a key driver in bringing coal mining to the valley and making the railway-and-mine plan real.

Once coal was being mined and rail transport was available, Fernie wasn’t just a camp—it became a magnet. Labour arrived. Skills arrived. So did the messy realities of a boomtown: tough working conditions, rapid construction, and the social friction (and cultural richness) that comes with sudden diversity.

A multicultural boomtown (early 1900s)

Coal towns don’t grow slowly. They surge.

Community history resources describe the mining network around Fernie expanding quickly—multiple mines, coke ovens, and nearby communities (Michel, Morrissey, Hosmer) pulled into a single industrial orbit.

One of the most important “Fernie truths” is that the town was never a single-story place. Immigration shaped it early, including substantial European communities (Italians among them) whose labour—and lives—became inseparable from the coal economy.

And it wasn’t only European immigration. Fernie’s heritage walk highlights How Foon, a Chinese entrepreneur associated with a building used for laundry, shoemaking, a café, and rentals—an imprint of Chinese Canadian life that’s easy to miss if you’re only looking for brick arches and mountain views.

The 1902 Coal Creek disaster (and the cost of coal)

Every mining town has grief in the foundation. Fernie’s is stark.

A major explosion at Coal Creek in 1902 is widely cited as one of Canada’s deadliest mining disasters—often reported around 128 deaths (you’ll sometimes see slightly different totals depending on how sources count injuries and later fatalities).

What matters for a traveler isn’t morbid curiosity—it’s context. Fernie’s handsome downtown and modern outdoor lifestyle weren’t “free.” They sit downstream from labour, danger, and community trauma. When you walk Victoria Avenue and think, this is cute, it’s worth also thinking, this place earned its survival the hard way.

Fire remakes Fernie (1904, then 1908)

If coal built Fernie, fire redesigned it.

A 1904 fire damaged much of the wooden commercial core; then the Great Fire of August 1, 1908 became the defining inferno—devastating Fernie in under 90 minutes.

And here’s the architectural plot twist: instead of rebuilding the same way, Fernie rebuilt differently. Local histories describe how the community was undeterred and reconstructed with brick and stone, setting the look of downtown that visitors now photograph like it’s a movie set.

Tourism Fernie even points out something wonderfully specific and human: on a heritage walk, you can sometimes spot the Great Fire’s lingering evidence—soot and smoke residue on brickwork.

Fernie doubles down on “civic confidence” (1909–1912)

After catastrophe, Fernie didn’t rebuild small.

The Fernie Courthouse story is almost unbelievable for a town that was literally erased by fire: detailed materials (brick, granite, sandstone, slate), stained glass, carved dogwood emblems, and a chateau-like presence that still anchors downtown. Tourism Fernie’s courthouse history lays out the post-fire push toward “fire-resistant” materials and the rebuilding timeline that followed.

Religious and community buildings also became long-term landmarks. The heritage walk lists Holy Family Catholic Church and ties it directly to the earliest mining-era community and donations from miners toward construction, completed in 1912.

War, internment, and the parts of history that don’t feel “touristy”

Fernie’s region is also connected to Canada’s First World War internment operations.

National-level documentation (Library and Archives Canada) records internment operations during this era, and Fernie’s heritage materials point visitors to a World War I Internment Memorial, linking the story to a camp that moved to Morrissey after an initial setup in Fernie.

This is one of those “walk slower” moments. It’s not a fun photo stop. It’s a reminder that Canadian history includes state power used harshly against people deemed “enemy aliens,” including many Ukrainians and other Europeans, often forced into labour.

The 1923 Home Bank collapse (a financial gut-punch)

If you want a single building that sums up Fernie’s whiplash—boom, tragedy, rebuild, betrayal—it might be the former Home Bank.

The Heritage Walk notes the building was constructed in 1910 to house a branch of the Home Bank (and a law office), and that its failure in 1923 cost Fernie depositors $800,000, contributing to major changes in Canadian banking law.

And the “then vs now” twist is perfect: that same building is now the Fernie Museum—so you step into the place where money once vanished, and you leave with history instead.

From underground roots to modern industry (mid-1900s to today)

Coal didn’t disappear. It shifted.

Fernie-area histories describe coal remaining a major pillar of the economy, with the industry sustained through hard years and then revitalized by broader world markets in the 1960s.

If you zoom out to the Elk Valley, mining becomes a “regional spine” rather than just a Fernie story—large-scale operations, global demand, and (in modern times) increasingly prominent conversations about environmental impact and water quality.

Tourism rises: the ski-town era (1962 onward)

Fernie’s reinvention didn’t happen by accident. It happened because locals built it.

Tourism Fernie’s ski history timeline records Fernie Snow Valley officially opening January 10, 1962 (with land donation and volunteer labour) and notes that the Chamber of Commerce began the process of bidding for the 1968 Winter Olympics—unsuccessfully, but with lasting momentum.

Then the modern resort era arrives: in 1997, the resort is purchased and renamed Fernie Alpine Resort, followed by major expansions in 1998 (chairlifts, bowls, village growth).

So yes, Fernie is a mountain playground now—but it’s also a town that had to keep rebuilding itself in the most literal sense.

Then vs now

| Topic | Then | Now | What it means for visitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economy | Coal extraction dominates; boom/bust cycles hit hard | Coal still matters, but tourism + services are huge | You can ski, hike, eat well—and still feel the industry in the region |

| Architecture | Early wood structures + rapid construction; high fire risk | Brick-and-stone heritage downtown with preserved guidelines | The “Old Town charm” is literally post-disaster design |

| People & culture | Immigrant labour communities, including Italians; Chinese Canadian entrepreneurship visible too | Outdoor-minded locals, seasonal staff, visitors; heritage preservation taken seriously | Fernie feels both lived-in and visitor-friendly, not like a theme park |

| Getting around | Rail + horse-drawn deliveries; tight downtown tied to industry | Car access + trail networks + walkable historic core | You can do history on foot, then switch straight into nature |

Our “we were there” scenes

1) Burritos first, history second (and that’s very Fernie)

We rolled into Fernie the way a lot of travelers do: hungry and curious. Lunch was downtown at Luchadora, the kind of casual place that instantly makes a mountain town feel like a real town (not just a resort base). Then we did the move we always promise ourselves we’ll do more often: museum before more wandering.

Because here’s the thing—Fernie’s “cute” isn’t random. The museum gives you the lens. Once you’ve seen the stories of coal, fire, floods, and reinvention, every brick façade downtown stops being just a backdrop and starts being evidence.

Practical nugget: If you’re only in Fernie for a quick weekend, do the museum early. It makes every later walk feel smarter.

2) Fernie Museum: the room where the town explains itself

At the Fernie Museum, we got hit (gently, but firmly) by the scale of what this little town has lived through: mine disasters, the 1904 fire, the 1908 firestorm, and the constant theme of rebuilding. The museum’s setting matters too—it’s the former Home Bank building, tied to the 1923 bank failure that burned depositors and rippled into national banking reforms.

It’s also wonderfully Fernie that admission felt accessible: we experienced it as by donation, and it didn’t feel like a rushed, sterile stop.

Practical nugget: Pair the museum with the heritage walk right after—your brain will start connecting dots in real time.

3) The heritage walk “click”: soot on brick and why downtown looks like this

The Heritage Walking Tour is where Fernie’s history becomes physical. Not abstract. Physical.

You’re walking a downtown that exists because the town was essentially erased in 1908 and rebuilt in brick and stone. Tourism Fernie even calls out that you can sometimes spot traces of the Great Fire—soot and smoke residue on brickwork.

That’s the “Fernie click” for a first-timer: the prettiest part of town was born out of catastrophe, and it’s been intentionally preserved ever since.

Practical nugget: Plan about 2 hours for the self-guided heritage walk at a relaxed pace.

4) Big Bang Bagels + the everyday Fernie that survives every era

Day two started at Big Bang Bagels—a real-deal local institution with that steady flow of regulars that tells you a town isn’t performing for tourists. We went for big flavours (the “Avalanche” situation for one of us, and a smoked salmon stack for the other), then pointed ourselves toward nature with the baby in tow.

It sounds simple, but it fits the theme: Fernie’s history is dramatic, but Fernie’s present-day charm is everyday. Good breakfast. Friendly pace. Then you’re off to trails.

Practical nugget: Grab bagels to-go if you’re heading straight to a hike—Fernie mornings fill up fast in peak seasons.

5) Fairy Creek Falls: a modern “resource town” lesson, told by terrain

Hiking to Fairy Creek Falls with the baby in the backpack was one of those Fernie-only moments: you’re in serious mountain terrain, but it’s still family-doable if you take your time. We noticed avalanche/terrain signage along the way—little reminders that the Rockies are beautiful and not remotely “cute.”

And that loops back to Fernie’s working-history DNA. This is a place built by people who lived with risk: first in mines, now in mountains. Different era, same respect required.

Practical nugget: Start at the visitor centre area for maps and trail intel—we experienced it as genuinely helpful (and yes, the washrooms mattered).

6) Beer, then Island Lake Lodge: Fernie’s reinvention in one afternoon

Post-hike, we cooled down at Fernie Brewing Co. with a Ridgewalk Red Ale—more of a pint-and-snack stop than a full meal (mentally file that away).

Then we drove up to Island Lake Lodge and had one of those lunches that becomes a travel highlight: ramen that weirdly snapped us back to Japan, a smashed-patty burger with “how is this this good?” energy, plus desserts that felt borderline dangerous in the best way.

This is Fernie’s “now” in a nutshell: a town that was built on coal and rebuilt after fire, now thriving as a place where you can stack culture + food + alpine beauty into a single day.

Practical nugget: Island Lake Lodge is scenic even just for lunch, but it’s also the kind of place you plan to return to with more time (we did).

Where to experience Fernie’s history in real life

Old Town / historic core

Fernie’s downtown heritage district is the easiest “history win” because it’s walkable and dense.

Museums & interpretive sites

The Fernie Museum is the anchor—both because of its exhibits and because the building itself is a piece of the 1910–1923 financial story.

Industrial / working history

The coal story isn’t a footnote. You’ll see it in place names, memorials, and the way Fernie talks about itself—honestly, and often with pride mixed with grief.

Religious / civic landmarks

The courthouse and churches aren’t just pretty—they’re “rebuild statements,” constructed when Fernie decided it was going to survive and look dignified doing it.

Practical table

| Place | Why it’s historically important | Time needed | Cost / tickets | Booking tips |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernie Museum (former Home Bank) | 1910 bank building; 1923 Home Bank failure; core Fernie history exhibits | 45–90 min | We experienced it as donation-based (verify current) | Pair it with the heritage walk immediately after |

| Heritage Walking Tour (16 stops) | Best “brick Fernie” overview; post-1908 rebuild story | ~2 hrs | Free | Pick up brochure at museum/visitor info |

| Fernie Courthouse | Post-fire “fire-resistant” rebuild era landmark; rare chateau-style courthouse | 15–30 min (exterior) | Free (exterior) | Best photos in morning/late light |

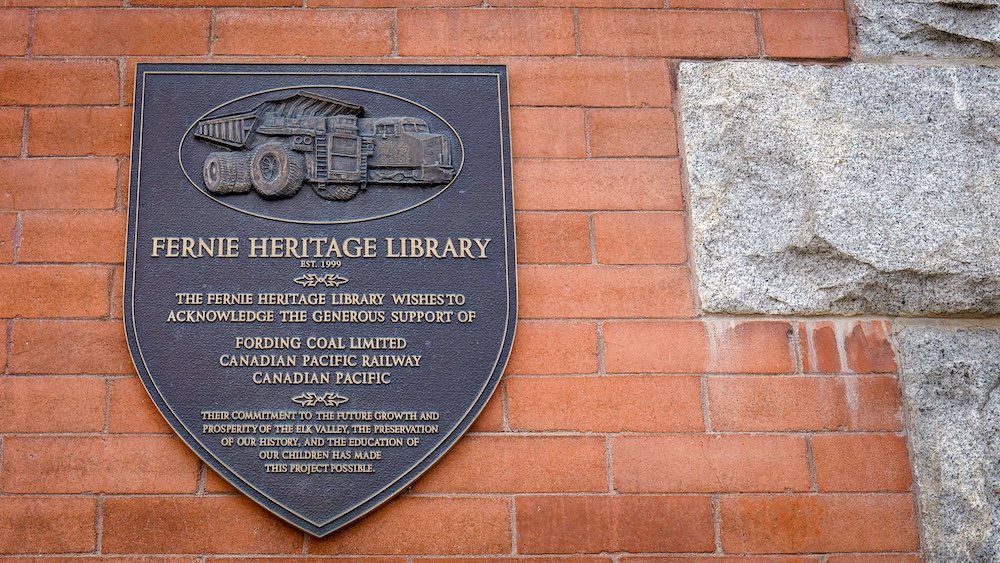

| Fernie Heritage Library (Post Office & Customs) | 1907 building; survived the 1908 Great Fire (gutted but not destroyed) | 10–20 min | Free | Look for Great Fire exhibit referenced in heritage materials |

| City Hall + Miner’s Walk (Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Co. building) | Coal company HQ building; refuge during/after 1908 fire; Miner’s Walk panels | 20–45 min | Free | Great family stop—easy, central, informative |

| WWI Internment Memorial | Connects Fernie to Canada’s internment history | 10–15 min | Free | Approach quietly—this is a heavy chapter |

A self-guided “history walk” route

Start: Fernie Museum (491 2nd Ave)

End: The Arts Station (CPR Station, 601 1st Ave)

Time: ~2 hours, easy pace

Parking: Downtown street parking + nearby lots (arrive earlier in peak seasons)

If you only do 3 stops

- Fernie Museum (Home Bank building)

- Courthouse exterior + grounds

- Post Office & Customs Office / library building

Optional route table (a “doable” loop):

| Stop | What to look for | Photo spot | Quick tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fernie Museum (Home Bank) | Bank-era building + the “why Fernie survived” exhibits | Corner façades + entrance details | Do this first so downtown makes more sense |

| How Foon’s Laundry (Elks Hall) | Chinese Canadian business imprint; mural advertising | Signage + exterior lines | Easy-to-miss—slow down |

| Courthouse | Chateau-style design + rebuild-era confidence | Front angle from Howland/4th Ave | Even exterior-only is worth it |

| Holy Family Catholic Church | Mining-era congregation roots; completed 1912 | Front steps + tower lines | Quick, meaningful stop |

| Post Office & Customs / Library | 1907 building; Great Fire exhibit noted | Stonework + windows | Step inside if open |

| City Hall + Miner’s Walk | Coal-company building; refuge in 1908; interpretive panels | Gardens + mining-themed displays | Great family-friendly stop |

| CPR Station / Arts Station | Rail town roots; station repurposed as arts venue | Platform lines + building profile | Perfect “history → culture” ending |

Common myths, mix-ups, and what’s actually true

| Myth / claim | What’s true | Why the myth exists | Best source |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Fernie’s bad luck came from a curse, full stop.” | There’s a long-running local legend around a “curse,” but it’s folklore—not a factual explanation for disaster | Towns use myth to cope with repeated tragedy | Fernie.com history discusses it as legend |

| “Fernie was founded in 1904.” | A settlement exists earlier; Fernie is commonly cited as founded in 1898 and incorporated in 1904 | People mix up “founded” vs “incorporated” | Tourism Fernie facts; BC Geographical Names |

| “The Great Fire killed lots of people.” | The 1908 Great Fire caused immense property loss, but accounts note no lives lost in the fire itself | The scale of destruction feels like it must include fatalities | Tourism Fernie Great Fire of 1908 |

| “Fernie’s historic look is just ‘old-timey charm’.” | The brick-and-stone core is a rebuild decision after repeated fires | Visitors see beauty and miss the reason | Fernie.com history; Tourism Fernie overview |

| “The museum is just exhibits—it’s not part of the story.” | The museum lives in the former Home Bank building; the 1923 failure hit locals hard | Buildings hide their previous lives unless someone tells you | Heritage Walk + Tourism Fernie museum history |

What surprised us most

- How “big city” the downtown feels for a small mountain town—wide streets, substantial buildings, and a layout that makes walking easy

- How quickly the story flips from cozy to intense: food-and-stroll to mine disaster and firestorm in minutes

- That the architecture isn’t just pretty—it’s basically Fernie’s scar tissue, built to last after the town learned the hardest lesson twice

- How much Fernie’s story reminded us of other BC small towns that had to reinvent themselves (we felt that personally, growing up in Gold River)

Practical tips for history-minded travelers

- Do the museum early: it gives every later walk more meaning (and it’s an easy 45–90 minutes).

- Heritage walk timing: morning or early evening light makes the brickwork glow; the loop is comfortable at ~2 hours.

- Guided vs self-guided: guided walking tours are offered in summer seasons and typically require booking ahead.

- Accessibility: downtown sidewalks are generally paved; some older entries/stairs vary by building—plan a flexible route.

- Respect notes: tragedies (mining deaths, internment history) deserve a quieter tone—treat memorials as memorials, not “content.”

- Blend history + nature: Fernie’s a perfect “museum → café → trail” town (we literally did that).

Further Reading, Sources & Resources

This article is grounded in our own time exploring Fernie’s historic core, museum exhibits, and heritage walk, paired with deeper reading to understand why this town looks and feels the way it does today. To support historical accuracy, timelines, and context beyond what you can absorb on foot, we’ve included the official tourism summaries, museum research pages, and national archival sources below.

These links are useful if you want to dig deeper into specific chapters—coal, fire, immigration, skiing, or wartime history—or verify details while planning your own visit.

Notes on accuracy

Fernie’s history is documented across multiple institutions, and small details (dates, counts, wording) can vary slightly depending on source focus. Where differences exist, we’ve leaned on official tourism summaries, museum research, and national archives, while keeping the storytelling rooted in place-based interpretation you can experience today.

- Tourism Fernie — An Overview of Fernie’s History Tourism Fernie

- Tourism Fernie — The Great Fire of 1908 Tourism Fernie

- Fernie.com — History of Fernie Fernie.com

- Fernie Musem – Fernie History Fernie Museum

- Tourism Fernie — History of Skiing in Fernie (timeline) Tourism Fernie

- Fernie Heritage Walk (Tourism Fernie PDF) — Self-Guided Tour + building notes Tourism Fernie

- Community Stories — When Coal Was King (Italians in Fernie / coal industry growth) Community Stories collection

- Library and Archives Canada — First World War internment operations Internment Camps