You’ve seen the logo on the Patagonia vests of tech bros in San Francisco. You’ve seen the silhouette tattooed on the calves of hikers who clearly own more carabiners than I do. You’ve probably even cursed the mountain’s name while dragging your tired carcass up the final, gravelly, soul-crushing kilometer of the Laguna de los Tres trail.

I certainly did.

When Audrey and I arrived in El Chaltén, we were full of what I like to call “unearned athletic confidence.” We had spent weeks eating our way through Argentina—consuming enough empanadas to technically be considered 40% pastry by volume—and we assumed we could just waltz up to the base of this legendary peak.

Spoiler: We did make it. But somewhere around kilometer nine, while I was fantasizing about being airlifted out by a rescue helicopter (or at least carried down in a sedan chair), I looked up at those granite spires and thought: Who looked at this terrifying rock and decided to name it after a British guy?

Because that’s the weird part. Fitz Roy. It sounds like a posh butler or a specialized tea blend. It does not sound like a jagged, wind-scoured tooth of rock at the end of the world.

So, being the curious (and sore) traveler that I am, I dug into it. And what I found wasn’t just a boring geography lesson. It’s a story involving a “smoking” volcano that wasn’t, a moody sea captain with a coffee obsession, the invention of the weather forecast, and the glorious irony of naming a mountain after a man who likely never even set foot on it.

Welcome to the history lesson you didn’t ask for but absolutely need—especially if you want to sound smarter than your hiking buddies while you’re all catching your breath at Laguna Capri.

Part 1: The “Smoking” Mountain (Before the British Arrived)

Long before European explorers showed up with their flags, their maps, and their knack for renaming things they didn’t discover first, the peak already had a name. And honestly? It was a much cooler name.

The Aonikenk (Tehuelche) people, who had roamed these windy steppes for thousands of years, called it Chaltén (or Chaltel).

In their language, this translates roughly to “Smoking Mountain” or “Blue Mountain.”

Now, if you’ve been to El Chaltén, you know exactly why. The summit of Fitz Roy is almost perpetually snagged by clouds. Even on a “clear” day, there is often a wispy, white pennant trailing off the top, whipped into a frenzy by the Patagonian wind. To the Aonikenk, looking up from the valley floor without modern meteorological knowledge, this looked exactly like volcanic smoke.

They believed the mountain was a volcano—a sacred, angry, living thing that breathed fire (or at least steam) into the sky.

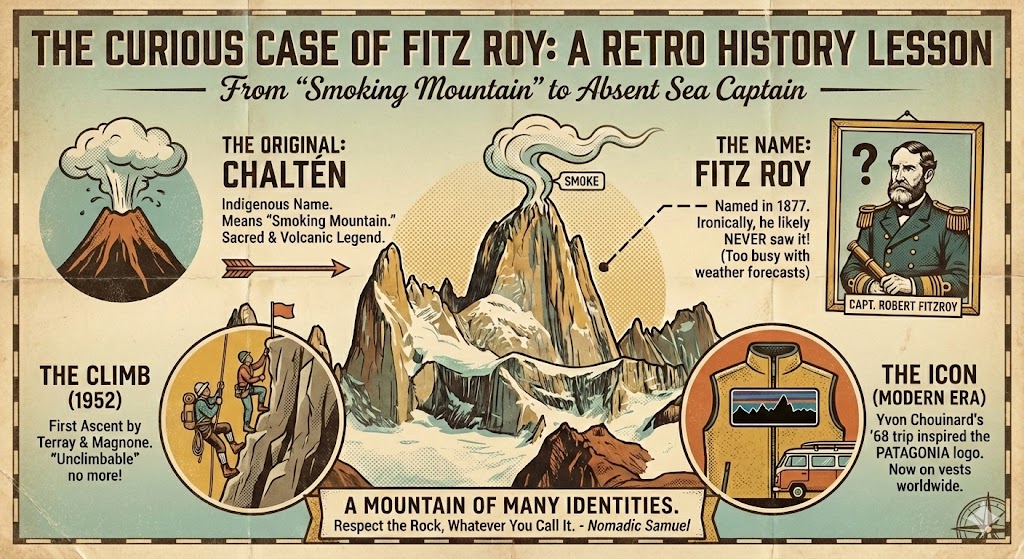

The Curious Case of Fitz Roy: A visual timeline from the 'Smoking Mountain' legends of the Aonikenk to the modern icon seen on vests worldwide.The Name Face-Off: Indigenous vs. Colonial

A quick breakdown of the mountain’s dual identity crisis.

| Name Version | Origin / Language | Literal Meaning | The “Vibe” | Nomadic Samuel Verdict |

| Chaltén | Aonikenk (Tehuelche) | Smoking Mountain / Blue Mountain | Mystical, elemental, dangerous volcano energy. | Winner. It describes exactly what you see when you look up. |

| Fitz Roy | Francisco Moreno (1877) | Tribute to Captain Robert FitzRoy | Formal, British, cartographic, polite. | Runner-Up. Sounds like a fancy tea blend, not a granite spire. |

The Mythology Twist: Elal and the Swan

To the Tehuelche, this wasn’t just a geological feature to be conquered or photographed for Instagram. It was the center of their cosmology.

The legend tells of Elal, the great cultural hero of the Tehuelche people (think of him as a mix of Hercules and Prometheus). Elal was born in a faraway land, but his father—a giant who was terrified that his son would overthrow him—wanted to kill him.

To escape, Elal was carried across the sea on the back of a majestic swan. Where did they land? You guessed it: right on the spiky summit of Chaltén. The mountain served as his fortress and his entry point into Patagonia. From there, Elal descended into the valleys to teach the Tehuelche people the secrets of survival: how to hunt the choique (Darwin’s rhea), how to make fire to survive the brutal winters, and how to construct bows and arrows.

So, for centuries, this peak wasn’t a challenge for alpinists. It was “Mount Olympus.” It was the landing pad of a god.

Nomadic Samuel Reality Check:

While hiking the Laguna Torre trail, Audrey and I walked through sections of “haunted forest” where the Lenga trees grow sideways, twisted by the wind. It’s easy to see how legends are born here. The landscape feels alive, hostile, and magical all at once. If someone told me a hero rode a swan onto the peak while I was struggling to open my granola bar in 80km/h gusts, I’d probably believe them.

Part 2: The Baptism (Why “Fitz Roy”?)

If the local name was so perfect, why do we call it Fitz Roy?

Fast forward to March 2, 1877. Enter Francisco “Perito” Moreno.

If you travel anywhere in Argentina, you will learn the name “Perito Moreno.” It is on the famous glacier we visited in El Calafate. It is on streets in Buenos Aires. It is on national parks. He is essentially the Beyoncé of Argentine exploration—everywhere, iconic, and impossible to ignore.

Moreno was exploring the Santa Cruz river valley, mapping the vast, undefined borderlands of Patagonia. When he laid eyes on the granite giant, he decided it needed a distinct name on his charts. He knew about the indigenous name “Chaltén,” but he argued that the term was being used too loosely by other explorers to refer to any volcano or jagged peak in the Andes. He wanted something specific, something that would lock this particular mountain onto the map forever.

So, he chose Mount Fitz Roy.

The Ultimate “Employee of the Month” Award

Moreno named the mountain to honor Captain Robert FitzRoy, the legendary captain of the HMS Beagle.

Here is the glorious irony that I love: Robert FitzRoy likely never saw the mountain.

Decades earlier, in 1834, FitzRoy and a young Charles Darwin had sailed the Beagle up the Santa Cruz River. They were on a mission to map the interior. They got incredibly close—within about 30 miles of Lake Argentino—but they ran low on supplies and the river current was brutal. They turned back before they could clearly identify or map the specific peak that would later bear the captain’s name.

Moreno named it after him anyway. He wanted to honor the British cartographic work that had laid the foundation for his own explorations. It was a professional nod—a hat tip from one navigator to another across time.

So, the most famous mountain in Argentina is named after a guy who got close, gave up because he ran out of biscuits (a feeling I relate to deeply), and went home.

Part 3: Who Was Robert FitzRoy? (The Man Behind the Mountain)

If you think you get cranky when you skip your morning caffeine, you haven’t met Robert FitzRoy.

To understand the mountain, you have to understand the man. And honestly? Robert FitzRoy is a fascinating, tragic character who deserves way more than just a name on a map.

The “Hot Coffee” Captain

FitzRoy was a nobleman, a brilliant navigator, and a man with a temper so explosive his crew nicknamed him “Hot Coffee”—because he could boil over in seconds and scald anyone nearby.

He was a perfectionist. He was obsessive. And he was deeply lonely.

That loneliness is actually the reason we have the Theory of Evolution. (Stick with me here).

In the 1830s, the captain of a British naval vessel was a lonely god. He couldn’t socialize with his crew because it would break the chain of command. FitzRoy knew he had a multi-year voyage ahead of him on the HMS Beagle, and he was terrified of succumbing to the depression and suicide that had plagued his own family (his uncle, Viscount Castlereagh, had famously taken his own life).

FitzRoy needed a companion. Someone of his own social class. Someone smart enough to talk to, but who wasn’t technically “navy” so they could be friends.

He interviewed a young, aimless naturalist named Charles Darwin.

Character Select: The Key Players

If this history lesson were a video game, these would be your playable characters.

| Character | Role | Superpower | Fatal Flaw / Weakness | Irony Level (1-10) |

| Elal | Tehuelche Hero | Riding giant swans; inventing fire. | Issues with his dad (a giant). | 0/10 (Pure Legend) |

| Robert FitzRoy | Sea Captain | Inventing the weather forecast; navigating the globe. | Evolutionary theory; running out of biscuits. | 10/10 (Never saw the mountain named after him) |

| Perito Moreno | The Explorer | Naming things; walking really far. | Naming majestic peaks after people who weren’t there. | 5/10 (He tried his best) |

| Lionel Terray | French Alpinist | Climbing vertical granite in leather boots. | Gravity; freezing winds. | 2/10 (Earned the glory the hard way) |

The Odd Couple

FitzRoy brought Darwin on board to keep him sane. Ironically, the voyage ended up driving a wedge between them that would last a lifetime.

FitzRoy was a devout, literalist Christian. He believed every word of the Bible was fact. Darwin, meanwhile, spent five years on FitzRoy’s boat collecting beetles, finches, and fossils that would eventually dismantle that entire worldview.

Imagine spending five years in a tiny wooden cabin with a guy whose diary is slowly destroying everything you believe in. That was FitzRoy’s life. He provided the ship, the navigation, and the safety that allowed Darwin to formulate the Theory of Evolution—and he hated it. Years later, at the famous Oxford debate on evolution, FitzRoy reportedly stalked around the back of the room holding a Bible over his head, shouting, “The Book! The Book!” begging people to listen to scripture instead of his former friend.

The Weather Wizard

While he didn’t climb the mountain, FitzRoy did something arguably cooler for us travelers: he invented the weather forecast.

After retiring from the sea, FitzRoy was appointed as a chief statistician for the government. He was horrified by how many sailors were dying in storms around the UK because they had no warning.

He set up a network of weather stations that could telegraph data to London instantly. He analyzed the patterns. He designed a new type of barometer (the “FitzRoy Barometer”) that could hang in every port. And he began publishing “probable weather” reports in the newspapers.

He even coined the term “forecast.”

Before him, predicting the weather was considered astrology or witchcraft. He made it a science. He saved thousands of lives.

Nomadic Samuel Reality Check:

On Day 4 of our trip, El Chaltén was hit by winds so ferocious we literally couldn’t stand up straight. We abandoned our hiking plans and retreated to La Waflería to eat gourmet waffles and play cards. As the wind howled outside, shaking the windows, I realized we were experiencing exactly what FitzRoy spent his life trying to predict.

It felt fitting. The mountain named after the father of weather forecasting is located in the windiest place on Earth. It feels like the universe has a sense of humor.

The “Odd Couple” Friction Matrix: FitzRoy vs. Darwin

They spent 5 years on a boat together. It didn’t end well.

| Category | Captain FitzRoy 🌧️ | Charles Darwin 🐢 | The Friction Point |

| Worldview | Strict Creationist (Bible is literal fact). | Curious Naturalist (Questioning everything). | Darwin’s beetles and bones were slowly dismantling FitzRoy’s religion. |

| Job on Boat | Keep everyone alive; Map the coast. | Collect bugs; Be a companion. | FitzRoy worked; Darwin wandered. |

| Legacy | Weather Forecasting & Barometers. | The Theory of Evolution. | FitzRoy hated that his ship enabled “The Origin of Species.” |

| Temperament | “Hot Coffee” (Explosive). | Patient and observant. | Living in a tiny cabin for 5 years with opposite personalities. |

The Final Tragedy

Despite his brilliance, FitzRoy was mocked in his lifetime. The newspapers made fun of his “forecasts” whenever they were wrong (because complaining about the weatherman is a tradition that started in 1860). He lost his fortune trying to fund his own inventions. He was tormented by the role he played in aiding Darwin’s “heresy.”

In 1865—twelve years before Moreno would name the mountain after him—Robert FitzRoy locked his door and took his own life. He died broke and feeling like a failure, never knowing that his name would one day be synonymous with the most beautiful peak in the Southern Hemisphere.

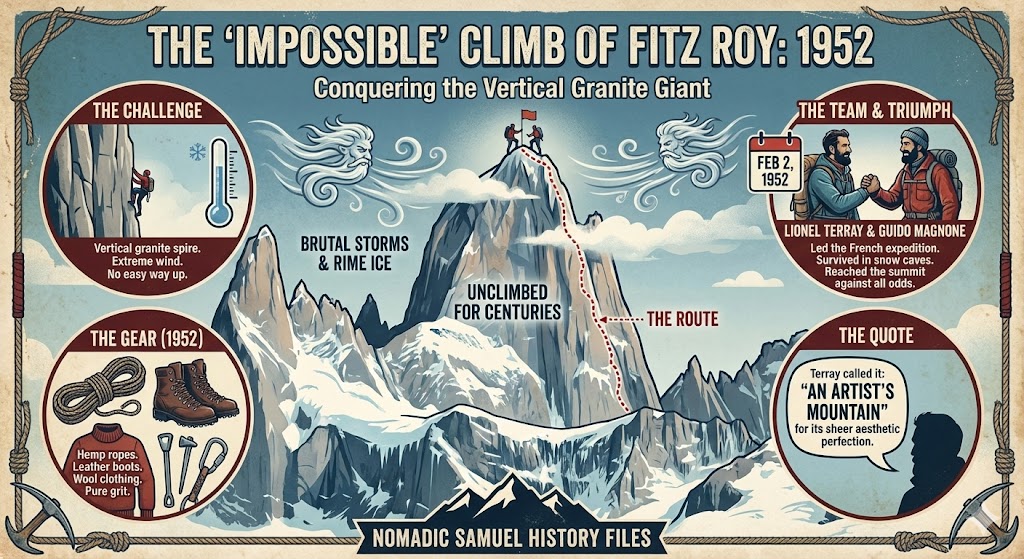

Part 4: The “Impossible” Climb

For decades after it was named, Mount Fitz Roy was just a drawing on a map. Nobody thought it could be climbed.

It’s not the height that’s the problem. At 3,405 meters (11,171 ft), it’s actually not that high compared to giants in the Himalayas or other Andean peaks like Aconcagua.

The problem is the shape. And the wind.

Fitz Roy is essentially a vertical shard of granite protected by an ice cap and surrounded by the worst weather on the planet. The wind doesn’t just blow; it screams. It coats the rock in “rime ice” (frozen fog) that makes handholds disappear.

It wasn’t conquered until 1952.

To put that in perspective: Humans had reached the North Pole (1909), the South Pole (1911), and nearly the top of Everest (attempts were well underway) before anyone stood on top of Fitz Roy. It was one of the last great prizes of alpinism.

The French Conquest

A French expedition led by Lionel Terray and Guido Magnone finally cracked the code. But it nearly broke them.

They didn’t just walk up. They had to siege the mountain. They dug snow caves at the base to survive the storms. (That spot is now Campamento Poincenot, the campground Audrey and I walked past on our way to the lagoon. It’s named after Jacques Poincenot, a member of their team who tragically drowned in the river during the approach).

Terray and Magnone climbed with hemp ropes and heavy leather boots—gear that makes my modern trekking poles and Gore-Tex look like sci-fi technology. When they finally reached the summit on February 2, 1952, Terray famously called it “an artist’s mountain” because of its sheer aesthetic perfection.

Myth vs. Science Reality Check

Why is there smoke on the water (or mountain)?

| Perspective | The Explanation | Why it makes sense |

| The Aonikenk Myth | It is a volcano releasing smoke and ash from the earth’s core. | The clouds are white, wispy, and attach to the peak exactly like a plume. |

| The Modern Science | “Orographic Lift” causing condensation at the summit. | Moist Pacific air hits the rock, is forced up, cools, and forms a permanent cloud banner. |

| The Hiker’s Reality | “The mountain is judging us.” | If the cloud is there, you can’t see the peak you just walked 10km to see. |

Nomadic Samuel Reality Check:

When Audrey and I hiked the final kilometer to Laguna de los Tres, we were struggling. I mean, really struggling. It’s steep, it’s gravelly, and the wind tries to push you off the mountain.

I remember stopping to catch my breath (read: dry heave quietly) and looking up at the spire itself. I tried to imagine climbing that vertical wall, in 1952, wearing wool sweaters and leather boots.

It instantly cured my complaining. Well, mostly. I still wanted a sedan chair, but at least I respected the history.

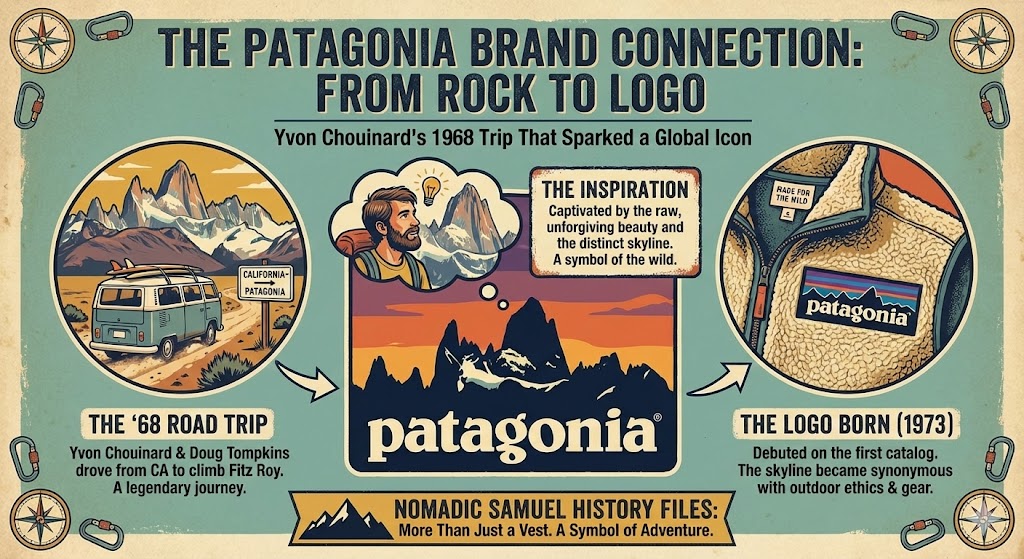

Part 5: The “Patagonia” Brand Connection

If you own a fleece vest, you are wearing a picture of this mountain on your chest.

In 1968, a young American climber named Yvon Chouinard (along with Doug Tompkins and friends) drove a van from California to Patagonia to climb Fitz Roy.

They put up a new route on the southwest ridge, now known as the “Californian Route.” The trip was a disaster and a triumph. They got battered by storms. They ran out of food. They spent weeks living in an ice cave (which they called the “ice womb”) waiting for the wind to die down.

But the experience changed Chouinard’s life. He fell in love with the raw, unforgiving beauty of the place. Years later, when he started his outdoor clothing company, he didn’t name it “Chouinard Gear.” He named it Patagonia.

He used the silhouette of the Fitz Roy skyline as the logo.

So, every time you see a tech bro in a Midtown finance office wearing a Patagonia vest, you are looking at the jagged profile of the mountain that almost killed the company’s founder.

Part 6: The Modern Identity Crisis (Fitz Roy or Chaltén?)

Today, the mountain lives a double life.

- On Maps: It is officially Mount Fitz Roy.

- In Culture: It is increasingly referred to as Cerro Chaltén.

There is a strong push in Argentina to reclaim the original indigenous name. The logic is sound: why name the most beautiful natural monument in the country after a British captain who never touched it, when the original name (“Smoking Mountain”) is so poetically accurate?

The town at its base—where we stayed—is named El Chaltén. It was founded hastily in 1985 (making it younger than the movie Back to the Future) specifically to secure the border against Chile. The government chose the name “El Chaltén” to cement the Argentine identity of the region.

You will see both names used interchangeably. The mountain appears on the provincial flag of Santa Cruz, and if you talk to locals, many will speak of “El Chaltén” with a reverence that “Fitz Roy” just doesn’t capture.

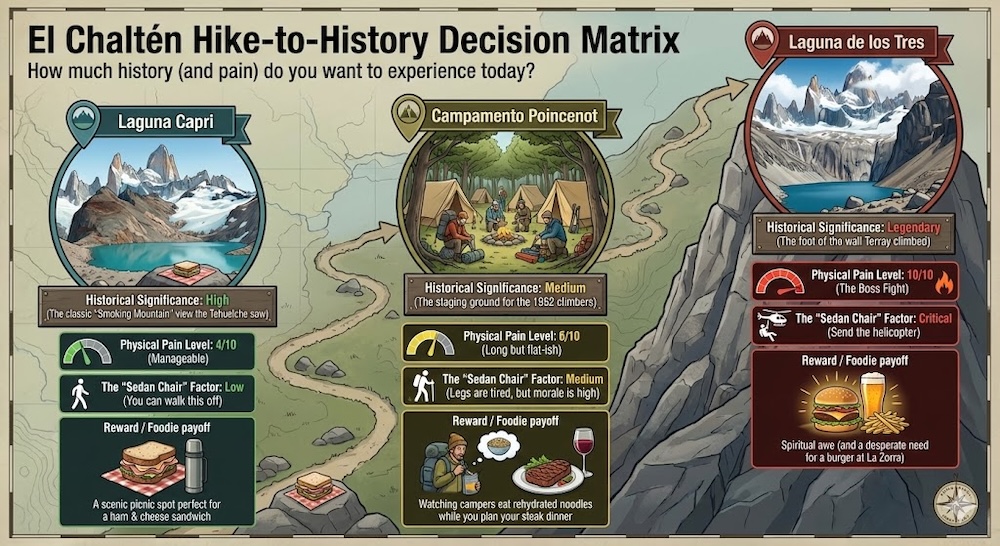

How to “Hike the History” (A Practical Guide)

You don’t need to be a French alpinist to experience this history. You just need a pair of boots and a tolerance for wind. Here is how to see the historical spots we mentioned:

Hike-to-History Decision Matrix

How much history (and pain) do you want to experience today?

| Hike Destination | Historical Significance | Physical Pain Level (1-10) | The “Sedan Chair” Factor | Reward / Foodie payoff |

| Laguna Capri | High: The classic “Smoking Mountain” view the Tehuelche saw. | 4/10 (Manageable) | Low: You can walk this off. | A scenic picnic spot perfect for a ham & cheese sandwich. |

| Campamento Poincenot | Medium: The staging ground for the 1952 climbers. | 6/10 (Long but flat-ish) | Medium: Legs are tired, but morale is high. | Watching campers eat rehydrated noodles while you plan your steak dinner. |

| Laguna de los Tres | Legendary: The foot of the wall Terray climbed. | 10/10 (The Boss Fight) | Critical: Send the helicopter. | Spiritual awe (and a desperate need for a burger at La Zorra). |

1. The “Smoking” View (Laguna Capri)

- The Hike: ~8km round trip (Intermediate).

- The History: This is the best spot to see the “smoke” effect. If you sit by the lake on a breezy day, you will see the clouds hooking onto the summit notch, exactly as the Tehuelche people saw it thousands of years ago.

- Nomadic Samuel Tip: We stopped here for lunch. It is paradise. If you are too tired to go all the way to Laguna de los Tres, stopping here is not a failure. It is a victory with a view.

2. The Climber’s Base Camp (Campamento Poincenot)

- The Hike: On the way to Laguna de los Tres (about 8km in).

- The History: Walk through the campground. This is the staging ground where Terray, Chouinard, and every modern climber has shivered while waiting for a weather window. It is hallowed ground.

- Nomadic Samuel Tip: Look at the tents. Look at the people eating ramen out of bags. Feel superior because you are going back to town to eat a burger at La Zorra. (We did. No regrets).

3. The “Boss Fight” (Laguna de los Tres)

- The Hike: ~22km round trip (Hard).

- The History: This brings you to the foot of the granite wall. You can look straight up the face that the 1952 expedition had to scale.

- Nomadic Samuel Tip: The last kilometer is brutal. It’s a stairmaster made of loose rocks. But when you get to the top and see that cobalt blue water against the grey rock, you understand why people travel across the planet to see it. Just bring layers—we hid behind a rock to eat our celebratory granola bar because the wind was trying to peel our faces off.

🤓 Nomadic Samuel’s “Did You Know?” Matrix

If you want to be the smartest person at the hostel dinner table tonight, memorize this table.

| Fact Category | The Detail | Why it’s cool/weird |

| The Nickname | “Hot Coffee” | FitzRoy’s temper was so explosive his crew named him after boiling liquid. |

| The Mythology | Elal & The Swan | The Tehuelche hero arrived on the peak riding a swan. Way cooler than a helicopter. |

| The “First” Ascent | 1952 | Fitz Roy was climbed after Annapurna. That is how technically difficult it is. |

| The Controversy | Darwin vs. FitzRoy | The captain hated evolution, yet his ship enabled the theory. He stalked Darwin with a Bible. |

| The Brand | Patagonia Logo | Yvon Chouinard climbed it in 1968 and used the skyline for his logo. It’s on your vest. |

| The Town | Founded 1985 | El Chaltén is remarkably young. Before ’85, there was almost nothing there. |

Conclusion: A Mountain by Any Other Name

So, when you are standing in El Chaltén, looking up at that jagged tooth of granite piercing the sky, what are you looking at?

Are you looking at Fitz Roy, a monument to British naval history and a tragic genius who invented the weather forecast?

Are you looking at Chaltén, the sacred, smoking volcano of the Tehuelche people and the landing pad of a god?

Or are you looking at the “Artist’s Mountain,” the ultimate prize that broke the hearts (and toes) of the world’s best climbers?

The answer, of course, is all of the above.

The Evolution of an Icon

How a rock became a brand.

| Era | Identity of the Mountain | Primary Audience |

| Pre-1800s | Sacred landing pad of Elal the Hero. | Tehuelche Nomads. |

| 1877 – 1950s | “Unclimbable” geographic curiosity. | European Cartographers. |

| 1952 – 1968 | The “Artist’s Mountain” / Alpinist Prize. | Elite French & American Climbers. |

| 1973 – Present | The Patagonia Logo. | Tech Bros in Vests & Weekend Hikers. |

Whatever you call it, just make sure you respect it. Bring your trekking poles. Bring your windbreaker. And for the love of all that is holy, bring extra snacks. Because whether it’s named after a sea captain or a smoking legend, that mountain doesn’t care about your hunger levels.

It just stands there, smoking in the wind, waiting for the next person crazy enough to walk toward it.

Planning a trip to see the “Smoking Mountain” yourself?

Check out our complete travel guide to El Chaltén or read about our brutal reality check on the Laguna de los Tres hike. Just don’t forget to pack a lunchbox—trust us, you’ll need the calories.

Fitz Roy (Cerro Chaltén) FAQ: the name, the people behind it, and what travelers get confused about

Why is it called Fitz Roy?

Because Argentine explorer Francisco “Perito” Moreno named the mountain “Fitz Roy” in 1877 to honor Captain Robert FitzRoy of the HMS Beagle. It’s one of those classic mapmaking moments where an existing local name gets replaced (or overshadowed) by a commemorative one.

Did Robert FitzRoy actually see the mountain?

Probably not in any clear, confirmed way. FitzRoy explored the Santa Cruz River region in the 1830s, but there’s no strong evidence he stood somewhere with a clean view of the peak we now call Fitz Roy—making the naming twist a little ironic.

Who was Robert FitzRoy, in plain English?

He was a British naval officer and a top-tier navigator who captained the HMS Beagle (yes, the Darwin voyage). He also became a major figure in early weather forecasting—so his name being tied to Patagonia’s famously moody skies feels strangely fitting.

What does “Chaltén” mean?

It’s commonly translated as “Smoking Mountain,” referring to how clouds and wind wrap around the summit and make it look like it’s steaming. Some sources also mention “Blue Mountain,” depending on linguistic interpretation and oral history.

Is “Chaltén” the original Indigenous name?

Yes—“Chaltén” (often linked to Tehuelche/Aonikenk usage) is widely treated as the older, locally rooted name tied to meaning and landscape. “Fitz Roy” arrives later as a formal label through exploration and cartography.

Why do some people say “Cerro Chaltén” instead of Fitz Roy?

Because “Cerro Chaltén” is a way of using (or restoring) the older name while still clearly referring to the same peak. You’ll see both in conversation, signage, and writing—sometimes even in the same sentence for clarity.

Is El Chaltén (the town) named after the mountain?

Yep. The town’s name reinforces how central the mountain is to the area’s identity—so even travelers who only hear “Fitz Roy” for the peak still end up saying “El Chaltén” all day long.

How do you pronounce Fitz Roy and Chaltén?

Fitz Roy: “fits-ROY” (pretty straightforward).

Chaltén: “chal-TEN” with the emphasis on the second syllable (and that crisp accent on the “én”).

Why did Perito Moreno choose the name Fitz Roy?

Because FitzRoy was a major historical figure connected to exploration of the region (especially via the Santa Cruz River). Moreno was essentially anchoring a dramatic, unmistakable mountain to a well-known explorer’s legacy.

What’s the Darwin connection here?

Darwin was on the HMS Beagle voyage under FitzRoy’s command. So when people say “Fitz Roy is tied to Darwin,” it’s not that Darwin named the mountain—it’s that FitzRoy’s most famous historical association is captaining the voyage that helped shape Darwin’s thinking.

What does the Patagonia brand have to do with Fitz Roy?

Patagonia famously uses the Fitz Roy skyline silhouette as its logo. That single graphic choice helped turn the mountain into a global icon—so even people who’ve never heard of El Chaltén recognize the outline on jackets and hats.

Was FitzRoy a controversial figure?

He’s complicated. He was brilliant and influential, but also intense, politically charged, and personally troubled. If you’re telling the story, it’s fair to present him as historically important and human—without turning him into a saint or a villain.

Which name should we use in our article: Fitz Roy or Chaltén?

Best practice for travel readers is: introduce both once early (“Fitz Roy, also known as Cerro Chaltén”), then use one consistently so it doesn’t get confusing. If you’re discussing meaning, identity, and origin, “Chaltén” deserves real space—not just a footnote.

Where can visitors “see the history” in real life while hiking?

Anywhere you can get a clear view of the summit’s cloud-wrapped “smoke” effect—Laguna Capri and Laguna de los Tres are the big classics. The moment Fitz Roy reveals itself (or refuses to) is basically the whole naming story, live, in real time.